Have you recently received an ‘Exclusive Dinner Invitation’ from a company called Wenatex in the letter box?

The letter says:

In order to satisfy the ever-increasing demand, we would like to invite you and your partner as our personal guests to one of our entertaining information evenings, which includes a wonderful dinner. While dining…we will inform you about current trends and new scientific research into the subject of healthy sleep…attending guests will receive a fantastic gift as an additional thank you.

While reading this letter, my thoughts drifted to a hot day in Koh Samui in April 2010 and how my wife and I had been duped into giving up our afternoon in the hope we’d make some money for our back packing holiday. This is what I wrote in my journal:

Tuesday 6th April 2010: Chaweng Beach, Koh Samui:

“While walking back to our hotel room for an afternoon siesta, stopped by tanned English couple on motorbike. Gave us scratchy cards. Surprise! We’d won a great prize – cash, laptop, camera or dream holiday Next thing, we found ourselves in a cab on our way to 90 minute timeshare presentation…

That afternoon, after the sales presentation (so boring, the memory of it is completely erased from my consciousness, but it must have happened as it’s in my travel journal) we were shown around expensive holiday resorts, given free cocktails and then subjected to the “hard sell” for timesharing that would have cost tens of thousands of dollars.

When the salespeople finally gave up, we received our prize: a voucher for a holiday at a resort in Thailand, not valid for immediate use. My guess is everyone gets that voucher. (A year ago I found it in an envelope among some travel mementos. It had long-expired.)

It struck me that the psychology behind the Wenatex dinner invitation is almost exactly the same as that used in Thailand. You think you’re getting something for free (a fancy meal + gift or expensive prize) but what you really get is a cheap meal and a long (4 hours according to one account) lecture on the science of sleep all designed to make you part with thousands of dollars.

Wenatex Australia has been offering their free dinners all over Australia and New Zealand since coming here in 2002 from their home base in Saltzburg, Austria.

Their high pressure selling techniques were reported on NZ current affairs show, Fair Go, which snuck cameras and two reporters into a Wenatex dinner and information evening. The video showed a lady giving the sales presentation and suggesting, outrageously, that a Wenatex sleep system had cured a man previously confined to a wheel chair.

For more of the flavour of these evenings, you can read comments on consumer forums here and here (My suspicion is that some of the more favourable reviews are written by Wenatex staff.)

You can also read this blogger’s account of attending a Wenatex free dinner in Canberra in 2013.

So just how successful is Wenatex at signing up customers at these free dinners?

The answer, emphatically, is: Very!

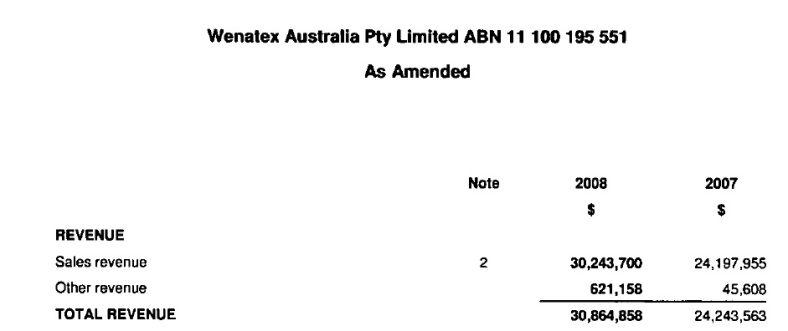

I obtained a copy of Wenatex Australia’s most recently filed annual accounts.

They show that for the 2007/2008 financial year the company earned a whopping $30.8 million (up 25% on the $24 million earned the previous year).

Assuming an average spend of $10,000 for a Wenatex sleep system, that’s more than 3,000 customers who have been convinced to part ways with a big chunk of money on a supposed free night out.

Assuming an average spend of $10,000 for a Wenatex sleep system, that’s more than 3,000 customers who have been convinced to part ways with a big chunk of money on a supposed free night out.

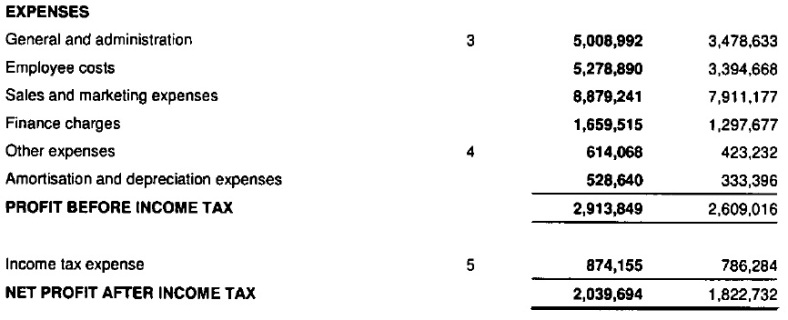

Profit for the year was a shade over $2 million with the biggest expense – not surprisingly – being sales and marketing (those free dinners) which totalled nearly $9 million.

Of the $2 million worth of after tax profit, nearly ($1.8 million) was paid to shareholders, which comprises a company called “Iways Pty Ltd”

Of the $2 million worth of after tax profit, nearly ($1.8 million) was paid to shareholders, which comprises a company called “Iways Pty Ltd”

There are four equal shareholders in Iways. They are Claude Wernicke, the CEO of Wenatex Australia, and presumably his sons – Stephen, Michael and Justin Wernicke.

Split four ways, the Wernickes each took home $450,000 in 2007/2008, that on top of any salaries earned. And that was five years ago. Given their rate of growth, they could conceivably be earning $1 million each by now.

Carpet salesmen-origins

The Wenatex sales strategy and the Thailand scratchy card/time-share ploy are essentially sophisticated, dressed-up versions of what you’ll experience if you venture into a carpet shop or trinket store in Morocco, Egypt or India – where you will be offered free tea, and a tour of the factory “just to look” before the big sales pitch and relentless bargaining begins and previously very friendly shop owner turns less so. (In Essaouira, Morocco in 2010, my wife and I found ourselves having our photos taken dressed up in full traditional Bedouin costumes before having carpet after carpet thrown at our feet despite out protests.)

Of course – just as we did from that carpet shop, you can go along to the Wenatex dinner, stuff your belly, listen to their spiel and walk away – or buy (as some do) a very expensive mattress.

I am not suggesting the Wenatex mattresses are not comfortable (they may even be superb), but unless you genuinely want to spend thousands of dollars for a mattress and accessories I’d suggest the following:

Tear up the Wenatex invitation, splash out a $100 of your own money and enjoy a guilt-free, relaxing, bona fide dining experience at a restaurant of your choice.

(And if you DO need a new mattress, head to the shops and try out as many as you like.)