Had he lived, Jim Morrison would have turned 70 this year. He was born on December 8, 1943 – 2 days and 30 years before me.

Had he lived, Jim Morrison would have turned 70 this year. He was born on December 8, 1943 – 2 days and 30 years before me.

As I remembered it, I hardly knew who Jim Morrison was before I saw the movie “The Doors” directed by Oliver Stone.

It came out in March 1991 so I would have been 17, in my final year of high school.

I remember, such was my musical naivety at the time, that I kept on confusing “Van Morrison“, the Irish folk singer with “Jim Morrison“, the hard-drinking, poetry-spouting Dionysian rock-god.

I wince now, thinking about it.

When the movie came out, I was instantly hooked by the chanting crowds, frenzied stage performances, the imagery – shamans, American indians, acid trips in the desert, the wild women and the enigma of Jim Morrison (as played by Val Kilmer) the American poet who burned so brightly and briefly.

Against this backdrop was the music, songs like “Light my fire”, “Touch me”, “Riders on the Storm” and the hypnotic, transcendental and surrealist masterpieces “The End” and “When the Music’s Over”.

This is the end. Beautiful friend.

This is the end. My only friend, the end.

Of all elaborate plans, the end.

No safety, or surprise, the end.

I’ll never look into your eyes…again.

The very first Doors album I bought was the double CD ‘The Best of the Doors’ featuring the famous “Young Lion” photo of Jim Morrison on the cover, taken by Joel Brodsky.

I am pretty sure I bought it while on Contiki in Europe, along with The Commitments soundtrack, which came out the same year.

After, that I bought the six studio albums The Doors recorded between 1967 and 1971 starting with the self-titled ‘The Doors’ and ending with ‘L.A. Woman’. They were all in the discount rack (39 rand back then) at a legendary CD joint called CD Wherehouse in Rosebank, Johannesburg, an enormous shop heaving with CDs in every available space – think JB Hi Fi on steroids.

(Side note: during a particularly confused/directionless period in my life – perhaps inspired by Jim Morrison – I dropped out of university to write a book. I got a job at CD Warehouse. The first day I packed away CDs. The second day I quit. It was my first and only brief dalliance with the world of retailing. The book never happened either).

In these studio albums were gems that hardly get any radio play, songs like the mournful “End of the Night, the melodic, whispery “Yes, The River Knows”, “Wishful, Sinful” and unsettling “The Spy”.

I’m a spy in the house of love

I know the dream, that you’re dreamin’ of

I know the word that you long to hear

I know your deepest, secret fear

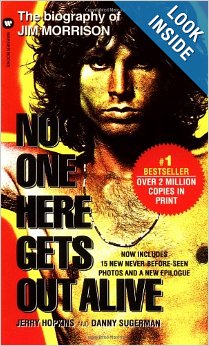

Then I bought the double CD ‘In Concert’, rented every live concert video I could find (this was long before there was YouTube), and read the classic best sellling biography of Jim Morrison by Jerry Hopkins and now deceased band manager Danny Sugerman: ‘No one here gets out alive.’

One of the last things I purchased was “Jim Morrison: An American Prayer” a haunting collection of Jim Morrison’s poetry with music by The Doors, released after his death in 1978. I was mesmerised by it with lines like:

A vast radiant beach in a cool jeweled moon

Couples naked race down by its quiet side

And we laugh like soft, mad children

Smug in the wooly cotton brains of infancy

Re-watching the movie

I recently watched the movie again.

I love the beginning: Jim Morrison, alone in a recording studio towards the end of his life recording poetry for ‘An American Prayer’. Morrison is overweight, sports a thick-beard and is unrecognisable from the skinny ‘Young Lion’ of a few years prior. He drinks from a bottle of whiskey and recites:

Is everybody in?

Is everybody in?…(softly and slowly)…

Is everybody in? (Pause) The ceremony is about to begin.

Then the film cuts to a sweeping panoramic shot over the desert in hues of red and dust as the words “The Doors” float up from the bottom of the screen accompanied by the opening piano trinklings of “Riders of the Storm”.

It’s a brilliant introduction.

Then follows the scene of the Morrison family driving past a car crash where a young Jim Morrison sees (as in the song Peace Frog):

“Indians scattered on dawn’s highway bleeding [and]

Ghosts crowd the young child’s fragile eggshell mind”

Then, its 1965. We find 22-year-old Jim Morrison strolling along Venice Beach, a book of poetry in hand. Later he meets and seduces Pamela Courson (a ditzy Meg Ryan) who will be his muse and lover.

Later, we find him back on the beach, hanging out with Ray Manzarek (Kyle MacLachlan) talking about Bob Dylan, the Vietnam War (“People want to either fuck or fight”) and making music.

Jim Morrison tells Manzarek he’s been writing songs and poems and then he sings a verse of “Moonlight Drive”:

Let’s swim to the moon, uh huh

Let’s climb through the tide

Penetrate the evenin’ that the

City sleeps to hideLet’s swim out tonight, love

It’s our turn to try

Parked beside the ocean

On our moonlight drive

The rest of the film tracks the rise of Jim Morrison and The Doors through the legendary live music clubs of Hollywood like the ‘Whiskey a Go Go‘ on Sunset Boulevard, their appearance on the Ed Sullivan show to larger and larger venues as ‘Mr Mojo Risin’ sinks deeper into drugs, alcohol and his eventual death in a Paris bath tub in 1973, aged just 27.

A shallow, vacuous film

When I saw the film in 1991, I thought it was a work of genius, but watching it again, almost 23 years later, I found it a shallow, vacuous film, despite excellent use of the music of The Doors and fine acting from Val Kilmer.

There is very little attempt to explain or explore who Jim Morrison really was. His motivations are all reduced to the impact of a witnessing a car crash when he was a small boy and a subsequent obsession with Indian shamans, Dionysus, acid trips and “breaking through to the other side” of regulated, orderly society.

It’s second great sin is that this really just a film about Jim Morrison with little interest in the other members of The Doors: Ray Manzarek, who created the band’s distinctive sound through his organ play, guitarist Robbie Krieger who wrote many of the songs including “Light my fire” (the band’s first No.1 single) and Roadhouse Blues and ranked 76th on Rolling Stone magazine’s list of the 100 greatest guitarists and John Densmore, who ranked 95th on the magazine’s list of greatest-ever drummers.

How did the Doors come to be? What were they trying to create? What inspired Jim Morrison’s poetry? What happened to his family? What shaped his view? None of these questions are answered.

“It’s a bloated, pompous, unbalanced film, which looks great but has nothing going on beneath the surface,” wrote the Guardian’s Alex von Tunzelmann in 2011 retrospective review.

What did other reviewers make at the time of its release?

The late great Roger Ebert wrote of the film that it was “not always very pleasant”.

“There are the songs, of course, and some electrifying concert moments, but mostly there is the mournful self-pitying descent of this young man into selfish and boring stupor,” wrote Ebert.

The Washington Post’s Hal Hinson wrote that what was most peculiar about the film was “Stone’s attitude toward his hero”.

“He’s indulging in hagiography (creating an idolised version of someone’s life), but of a very weird sort. A good part of the film is dedicated to demonstrating what a drunken, boring lout Morrison was…while on the one hand Stone…keeps implying that it’s all part of the creative process,” Hinson wrote.

But there was a softer, sensitive, almost childlike side to Jim Morrison.

Trawl through the countless Doors and Jim Morrison videos on YouTube and you’ll come across this short take of Jim Morrison playing cards with the other band members. It reveals a shy, sweet guy, not the monster who consumed everything put in front of him:

And there’s this video of Jim Morrison in thoughtful discussion with a priest about his music:

If Stone’s portrayal of Morrison is accurate, then the critics are right to damn him (Morrison) as a selfish, boring attention-seeker that must have been hell to work with.

The second part of Alex von Tunzelmann’s summation of the film is harsh: “This is the biopic Jim Morrison deserved,” she wrote.

Roger Ebert wrote: “Having seen this movie, I am not sad to have missed the opportunity to meet Jim Morrison, and I can think of few fates more painful than being part of his support system.”

Whether these remarks reflect Oliver Stone’s lack of balance and the film’s shortcomings or are more criticisms of the life Morrison led, is an interesting one to ponder.

For me, my fascination with both him and The Doors remains untainted. Rather I consider the film to be too dark, with not enough shades of light and colour.

Unlike Ebert, I would certainly have loved to have met ‘Mr Mojo Risin’ and shared a beer with him.