I went to hear legendary Scottish author Irvine Welsh speak last week.

I went to hear legendary Scottish author Irvine Welsh speak last week.

My friend Jonny, who has read all his books, invited me along to a talk hosted by the Wheeler Centre.

I have read just one of Welsh’s books, “Trainspotting”, but it was enough for me to say “yes” immediately.

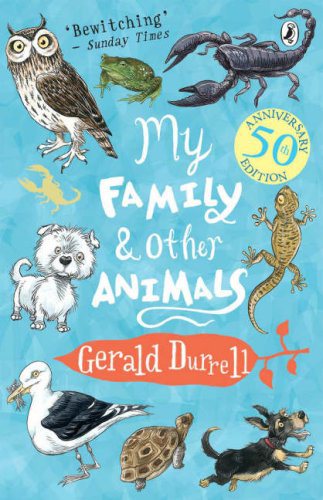

Trainspotting – a brilliant, excruciating, haunting and often hilarious story about a group of doomed Scottish junkies set in the impoverished council estates of Edinburgh in the late 1980s/early 1990s – was published in 1993 and has sold more than 1 million copies in the UK alone.

It’s listed in my literary reference bible: “1001 Books You Should Read before Die” alongside contemporary literary masterpieces by Salman Rushdie, Ian McEwan, Donna Tartt and J.M. Coetzee.

Welsh, a bald, tallish man sat down on stage at the Athenaeum Theatre on Collins Street dressed casually in a black t-shirt, jeans and leather jacket looking like the kind of guy you’d strike up a conversation with about football at the pub. The only sign of possible eccentricity: bright red socks.

He was there ostensibly to promote his latest book which has the intriguing title of ‘The Sex Lives of Siamese Twins’. It’s his first novel set entirely in the US – Welsh lives in Chicago and wrote and set the novel amongst Miami’s gym, fitness and dieting culture.

(“If people want to lose weight, they should just eat less. Instead, in America, they consume diets.” he says.)

It’s his first novel without a Scottish character with only the vaguest references to Scotland.

Putting on a bad American accent, Welsh recalled a line in the book spoken by one of the aggressive female characters to Wheeler Centre director Michael Williams:

“I don’t wanna go to a fillum set in Scotland or Bosnia speaking a language no one can understand.”

Williams reminded Welsh that he is had pronounced “film” in the Scottish dialect of “fillum”.

Welsh throws back his head and roars with laughter.

Miami agree with Welsh. He goes to gym, eats well, walks around in shorts and t-shirts taking in the good weather.

But his heart – thankfully – remains firmly rooted in Scotland, where he created his most iconic characters – Renton, Begbie, Sickboy and Spud.

It’s not just his heavy Scottish brogue that makes it hard to imagine he’s become an American in any way, he still clearly loves his homeland, telling the audience that he has enjoyed “discovering Scotland from the US”.

Moving to somewhere “exotic” like Miami, he says, made him realise that Scotland is “one of the f-cking weirdest places I have ever been to in my life.”

And he’s also kept up with local politics, noting that the country is “re-inventing itself from the inside out” and that it is an “exciting time” with the Scottish independence referendum vote on September 18 – a remark which draws a large cheer from fellow countrymen in the packed audience of devoted fans.

Welsh has also maintained that famous, sardonic, playful Scottish sense of humour, that made Trainspotting such a huge success.

He quips: “Scottish people are always wonderful to outsiders – they like people coming to visit, but they f-cking hate each other.”

He then jokes that the last time he visited Edinburgh everyone was so nice to each other, which meant he had nothing to write about.

This is thankfully an exaggeration with Welsh telling the audience that his next book – coming out next year – will be about a taxi driver in Edinburgh.

More than likely it will be about one of those failed characters, who he writes so well about – whether its Renton, Spud or Begbie in Trainspotting or the vicious Detective Seargeant Bruce Robertson in the recently filmed “Filfth” (a novel I’ve already picked up from the library).

Failure, is something which inspires Welsh and the characters he creates on the page: Trainspotting is not just about failed characters whose lives have been blown off course by heroin addiction but is set within a landscape of failure created by Margaret Thatcher and her Tory cronies, and one experienced by Welsh himself.

“Failure is much more interesting to me than success,” he says. “I write about people who are going through a bad time, when things are falling apart.

“I try to show these characters grasping for the light switch,” a beautiful phrase, which encapsulates the sadness behind doomed characters like Tommy Laurence, a football-mad childhood friend of Renton in Trainspotting who turns to heroin after his girlfriend dumps him and ends up contracting AIDS.

“These are people who were not always like what they are now,” Welsh says.

Welsh himself knows a lot about failure. He couldn’t play football or cut it as a musician (his two other passions) – but he was good at storytelling.

“Most writers are serial failures,” he says.

Speaking about his own success – he notes humbly that many celebrated Scottish writers blazed a path for him but did not achieve the international recognition he did.

He says he is inspired by bad fiction, rather than by what other great authors have written (one of his favourite books is Ulysses by Irishman James Joyce):

“When I read a shite book, I tell myself, I am going to take that c-nt down.”

Renton, couldn’t have said it better.