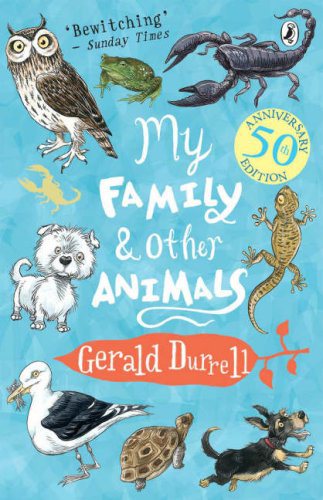

I had hardly thought of Gerald Durrell, the author and naturalist until my wife bought me his boyhood memoir “My family and other animals” as a gift.

I had hardly thought of Gerald Durrell, the author and naturalist until my wife bought me his boyhood memoir “My family and other animals” as a gift.

It tells the story of the four years he spent from 1935 to 1939 as a young boy living with his family on the Greek island of Corfu.

The family left the dampness and cold of London for the fresh air, sunshine and open spaces of the Greek island at the behest of Lawrence Durrell – Gerald’s oldest brother, who himself would go on to be a famous novelist, essayist and travel writer.

Picking up the book, I recalled a childhood memory of Gerald Durrell from a television show he presented that ran on South African television in the 1980s: a short, plump man with a white beard who appeared on television to tell us fascinating things about exotic animals. I looked at photos of him online and my memory served me well for he was indeed, short, plump and bearded.

The book is a wonderful account of an idyllic childhood for a young boy fascinating with nature. It’s one of the most entertaining books I have read, full of wonderful anecdotes about Gerry (as the family called him) and the animals he collects and brings into the family home.

These include: an owl, snakes (that end up being kept in the bath tub), frogs, a pigeon called Quasimodo, a tortoise and scorpions (that scatter one day across the floor during dinner) to name just a few.

Gerry Durrell is part Steve Irwin – unafraid to pick up creatures to see them up close – but more so Sir David Attenborough, with a wonderful eye for the details of nature and how it works plus the skills of a gifted novelist to bring it all to life.

In one scene he describes a gecko who has come to live in his room, which he names Geronimo:

He would sit on the window sill gulping to himself, until it got dark and a light was brought in; in the lamp’s golden gleam he seemed to change colour from ash-grey to a pale translucent pinky pearl that made his neat pattern of goose pimples stand out and made his skin look so fine that you felt it should be transparent so that you could see the viscera, coiled neatly as a butterfly’s proboscis, in his fat tummy. His eyes glowing with enthusiasm, he would waddle up the wall to his favourite spot, the left hand outside corner of the ceiling, and hang there upside down, waiting for his evening meal to appear.

This wonderful gift for describing a scene and revealing the wondrous details and idiosyncracies of nature is found throughout the book.

It is a mix of boy’s own adventure (Gerry accompanied by his faithful dog Roger exploring the island with almost unlimited freedom in which “all discoveries” filled him with “tremendous delight”) accompanied by hilarious tales of family life – Larry and his arty friends invading the island, his diet-obsessed sister Margo and the adventurous, gun-mad Leslie.

The other wonderful aspect of the book are the lovable eccentric local characters: There’s Spiro, the Durrell’s taxi driver, “guide, mentor and friend” – a “short, barrel-shaped man” with a unique grasp of the English language and who adored the family, the tremendously fat and cheerful Agathi who taught Gerry peasant songs and the immaculately groomed, sparkly eyed, Dr. Theodore Stephanides, who became Gerry’s guide to the natural world plus a parade of doctors, housekeepers and tutors.

Durrell writes of an afternoon spent with Agathi outside her “tumbledown cottage high on a hill:

Sitting on an old tin in the sun, eating grapes or pomegranates from her garden, I would sing with her and she would break off now and then to correct my pronunciation. We sang (verse by verse) the gay, rousing song of the river, Vangelio and how it dropped from the mountains, making the gardens rich, the fields fertile and the trees heavy with fruit.

By the time I finished reading the book, I yearned for just a few days of Corfu sunshine and a walks among its hills, valleys, gently swaying Cypress trees and olive groves.

I challenge you to find a more charming, magical account of a childhood we should only dream of giving to our children.