Drive down the steep and winding Melbourne Road into Gisborne, the pretty rural town north of Melbourne, and you will see the old faded orange wreck emerging over the rise, behind the tall trees.

Drive down the steep and winding Melbourne Road into Gisborne, the pretty rural town north of Melbourne, and you will see the old faded orange wreck emerging over the rise, behind the tall trees.

Standing empty and neglected, covered in graffiti and surrounded by ugly temporary fencing, its terracotta chimneys cracked like teeth, the single story building still retains an aura of once being a grand Victorian home.

I drive past this crumbling old wreck almost every day, but only recently discovered its fascinating history after reading an article in The Age newspaper.

It’s called Macedon House and has stood at the entrance to Gisborne for more than 170 years, just 13 years after Gisborne was established as a sheep grazing town.

The article in The Age described how Macedon House was one of two heritage buildings in Victoria (the other Valetta House in East Melbourne) where the owners have been ordered to carry out urgent repairs or face heavy fines.

“Those lucky enough to own heritage assets have a responsibility to maintain them — and we’ll ensure they do,” said Victorian planning minister Richard Wynne.

Built in 1847, the single storey, rendered, bluestone building with a hardwood-framed roof covered by original shingles (now beneath a corrugated iron roof) was originally called Mount Macedon Hotel. It is according to the Victorian Heritage Council “a rare surviving example of an early Victorian hotel”.

The hotel was built by Thomas and Elizabeth Gordon to “service the needs of district squatters”, those pioneering farmers in the early days of the colony of Victoria. The hotel served them mutton, salted fish and damper (a type of crudely made white bread) plus of course, brandy and beer, according to the Gisborne Gazette.

However, when gold was discovered on the Victorian goldfields in 1851, the hotel lost much of its trade as thousands rushed past it in search of their fortune.

By 1867 (after Thomas Gordon had died suddenly in 1855) Mount Macedon Hotel was no longer licensed. It was then known as Macedon House and became a family home for the Gardiners until 1878, when Elizabeth Gordon returned to live there, caring for her six children, and orphaned niece and nephew.

From 1887 onwards it was a boarding house for many decades, as well as serving as consulting rooms for a dentist and as a school where one of Elizabeth’s daughters taught.

It was a family home again from 1960, before being classified by the National Trust in 1974. Later it served as a reception centre, various restaurants, rooms for the neighbouring Gisborne Bowling Club (who bought it for $190,000 in 1995) and as a Montessori school.

A cash cow

Various media reports suggest Macedon House has been vacant since 2004, with its condition gradually worsening due to vandalism and neglect.

The reason for this appears to relate to long-held but never realised plans to develop the large property into a retirement village.

Instead progressive owners have elected to sell and take the profits, as its land value has soared (along with all property in Gisborne), and leave the development risk to someone else.

Having bought Macedon House for $190,000 in 1995, the Gisborne Bowling Club made a tidy profit when they sold it for $250,000 in 1998 to Mainpoint, the family company of Eduard “Ted” Sent.

Dutch-born Sent was in 1998 chief executive of Primelife Corporation, a publicly listed company that at its height controlled $1.6 billion portfolio of retirement villages and aged care facilities.

Presumable Ted Sent planned to turn Macedon House into another retirement asset of Primelife Corporation, before he departed as CEO in 2002. (Primelife collapsed in 2006).

In 2014, Melbourne developer Brian Forshaw – a long time friend and business partner of Ted Sent – acquired Macedon House for $770,000.

In 2015, plans were drawn up for “Macedon House Retirement Village” with about 40 homes spread out across the 2.1 hectare site.

Then, last year, two caveats were placed on the title which suggest that Brian Forshaw had struck deals to sell Macedon House.

The first in January was with a company called Nuline Consulting, ultimately owned by Grace Sent (Ted Sent’s wife) and then later in September with wealthy Melbourne doctor and developer Gary Braude for a reputed $1.21 million.

However neither of these deals appear to have been completed , and with the state government demanding urgent repairs to Macedon House, approved plans for a retirement village have been abandoned.

Brian Forshaw recently put the old wreck back on the market asking $1.39 million with real estate advertising describes Macedon House as a “dilapidated heritage hotel”.

More recently its been listed as a mortgagee sale through Kennedy & Hunt Real Estate with an auction date set for August 4.

In their description, Kennedy & Hunt Real Estate, who are local Gisborne agents, highlight Macedon House’s rich history and importance and include a few beautiful old photos dating back to 1899 of the building in its prime, against the backdrop of farmland and the pointy top of Mt Macedon.

Let’s hope who ever buys it this time round will restore it to its former glory and pay homage to 170-plus years of Macedon House’s colourful history.

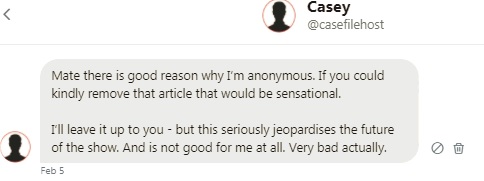

The global furore created by the data mining of 50 million Facebook users by controversial UK political consultants

The global furore created by the data mining of 50 million Facebook users by controversial UK political consultants  One of the most stunning podcast success stories in recent years, is

One of the most stunning podcast success stories in recent years, is

A new, hour–long, daily commute by train into work (Gisborne to Southern Cross) has suprisingly quelled my reading habits and instead created a new obsession: Podcasts.

A new, hour–long, daily commute by train into work (Gisborne to Southern Cross) has suprisingly quelled my reading habits and instead created a new obsession: Podcasts.

All the Light We Cannot See is a historical novel by American author Anthony Doerr that won the 2015

All the Light We Cannot See is a historical novel by American author Anthony Doerr that won the 2015

There’s a brilliant documentary floating about called

There’s a brilliant documentary floating about called

On the lookout for something bold and exciting to read, I browsed through my well-thumbed copy of 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die and came across The Master and Margarita by the Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov.

On the lookout for something bold and exciting to read, I browsed through my well-thumbed copy of 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die and came across The Master and Margarita by the Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov. This combination of cunningness and gentlemanly charm pervades the whole novel as Woland and his companions – the grotesque valet Koroviev; an enormous talking black cat called Behemoth (one of the best creations in fiction in my view), fanged hitman Azazello and an assortment of witches and other demons wreak all manner of chaos on Moscow’s disbelieving middle-classes.

This combination of cunningness and gentlemanly charm pervades the whole novel as Woland and his companions – the grotesque valet Koroviev; an enormous talking black cat called Behemoth (one of the best creations in fiction in my view), fanged hitman Azazello and an assortment of witches and other demons wreak all manner of chaos on Moscow’s disbelieving middle-classes. The horror is ratcheted up a notch as Bengalsky’s head is picked up and showed to the audience. “Fetch a doctor” the head moans. After promising to stop talking “so much rubbish” the head is plopped back on its shoulders as if it had never been parted.

The horror is ratcheted up a notch as Bengalsky’s head is picked up and showed to the audience. “Fetch a doctor” the head moans. After promising to stop talking “so much rubbish” the head is plopped back on its shoulders as if it had never been parted. I recently sat down over an informal lunch with a large real estate group in their high-rise office.

I recently sat down over an informal lunch with a large real estate group in their high-rise office. Zoo Time is another very funny, novel by Howard Jacobson, the writer of the Booker Prize-winning The Finkler Question (

Zoo Time is another very funny, novel by Howard Jacobson, the writer of the Booker Prize-winning The Finkler Question (