It’s been a couple of months since – aged 50 – I finished reading the Harry Potter series, and I have been meaning to jot down some thoughts ever since.

The reminder to put pen to paper, if you can forgive that rather useless and inappropriate cliché, came from an unlikely source: the columnist and writer, Clementine Ford.

Scrolling through my Instagram feed, I came across a three-year-old post from Ford in which she attempted to tear JK Rowling to shreds. Ford labelled her books “badly written” fiction and attacked “Joanne” for making her hero a boy wizard, where a girl (Hermione) does mostly all his homework for him, but gets no credit for it. Even more outrageous, Ford says, Hermione has no female friends, is overshadowed by all the boy characters and that all the female characters are “parodies of womanhood”.

Ford then gets stuck into her real issue with JK Rowling, the author’s controversial views on transgender people. Ford calls Rowling a “fucking scumbug” for harassing transwoman and suggests “Joanne” open up her “stupid fucking” castle and invite all her transphobic friends to live with her inside.

Ford’s disgust builds to a crescendo where she wonders how in the space of 25 years Rowling went from charming children’s worldwide to become one of her most sinister fictional character’s the cruel, toad-like Minister for Magic Dolores Umbridge who torments and tortures Harry Potter at Hogwarts.

This reference to one of JK Rowling’s most famous characters (and in my opinion one of the best written and fiendish across the series) made me wonder if Ford, who had just turned 40 at the time of the post, had not secretly enjoyed reading the books when she was younger, before finding herself disgusted by the controversy over Rowling’s views on womanhood and her alleged attacks against the transgender community.

Did JK Rowling become a bad writer and the Harry Potter story an unworthy cultural phenomenon because the author launched herself into the culture wars via posts on social media?

The answer is obviously no. JK Rowling is not a bad writer and her holding abhorrent views (to some) does not make her one.

Of course you may decide to boycott her books because of the things she says online, but it would be hard to argue that Harry Potter is not a great deal of fun to read. These are books that have entertained and delighted readers of all ages since the first in the series, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone came out in 1997.

Reading all seven books as I approached turning 50 and really enjoying them was something I had not expected.

I started reading the series because my daughter, Edie (12) was huge fan of all things Harry Potter and I thought it would be a great way for us to bond. After I finished each book, we’d watch the corresponding movie and discuss our thoughts of the big screen adaptation, the actors chosen to play the fictional characters, the bits in the books the films left out but that should have been kept in, the way the filmmakers had created the magical scenes and if the movies were any good. Mostly I enjoyed the films, but they were not a patch on the books (And there is now a HBO TV series in the works that we are told will be a more faithful rendition of the novels, with a full season devoted to each book).

For someone who reads “serious fiction’ and hardly anything in the fantasy genre, I was surprised at how much I enjoyed the novels. Whatever you think of Rowling’s views on gender, only a cynic would argue that Rowling is not a fabulous storyteller with the ability conjure up a complete magical world with a huge cast of living and breathing characters that have become cultural icons in their own right: Harry, Hermione, Ron, Hagrid, Malfoy, Professors Dumbledore, McGonagall and Snape (to name just few).

I also loved how the novels shifted between the fabulous wizarding world with its potions, ancient books and magic spells and the mundane “muggle” (human/non-magic) world inhabited by the wonderfully awful Dursleys (Harry’s relatives and tormentors).

But rather than write a lengthy review of each Harry Potter book – who needs another one of those? – my thoughts turned to the author and the culture wars she has sparked with her views on transgender issues and her strident defense of womanhood.

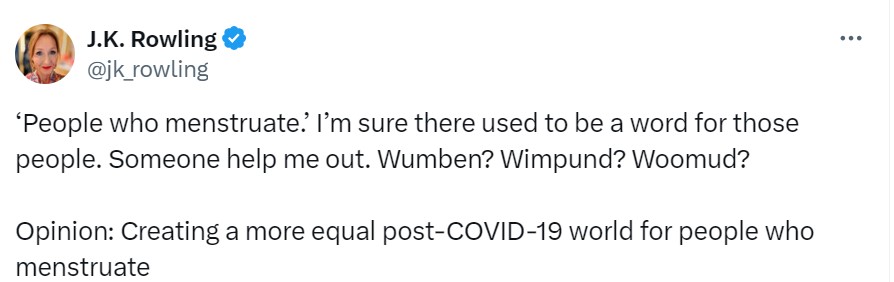

The controversy started back in 2020, when Rowling (rather petulantly in my view) took issue with an online article on Devex (a news organisation covering global development) about menstruation that did not in its opening pars mention woman, but instead used the gender neutral “people”. Later it refers to the 1.8 billion people who menstruate as “girls, women, and gender non-binary persons”.

Rowling responded to the controversy by saying: “If sex isn’t real, there’s no same-sex attraction. If sex isn’t real, the lived reality of women globally is erased. I know and love trans people, but erasing the concept of sex removes the ability of many to meaningfully discuss their lives. It isn’t hate to speak the truth,” she tweeted.

Rowling argues that she has been empathetic to trans people “for decades” and that feeling kinship for woman and believing that sex (or gender) is real, does not translate into hate for the transgender community.

She goes on to say: “I respect every trans person’s right to live any way that feels authentic and comfortable to them. I’d march with you if you were discriminated against on the basis of being trans. At the same time, my life has been shaped by being female. I do not believe it’s hateful to say so.”

Following the avalanche of abuse she suffered because of her social media posts, Rowling penned an article on her website explaining in great detail her position, her concerns for young people who may regret transitioning, her affection and acceptance of transgender people and her views on trans activists. whom she says are “doing demonstrable harm in seeking to erode ‘woman’ as a political and biological class”.

“I stand alongside the brave women and men, gay, straight and trans, who’re standing up for freedom of speech and thought, and for the rights and safety of some of the most vulnerable in our society: young gay kids, fragile teenagers, and women who’re reliant on and wish to retain their single sex spaces,” she writes.

As a survivor of domestic abuse and sexual assault, Rowling ask that the empathy for trans people “be extended to the many millions of women whose sole crime is wanting their concerns to be heard without receiving threats and abuse”.

However, she has received the harshest condemnation from some in the trans community for suggesting that some people, especially younger people may be “persuaded” to transition to “escape womanhood” or to find a more caring community, rather than because they suffer from gender dysphoria, a medical condition referring to the distress a person feels at one’s biological or assigned gender at birth.

“The more of their accounts of gender dysphoria I’ve read, with their insightful descriptions of anxiety, dissociation, eating disorders, self-harm and self-hatred, the more I’ve wondered whether, if I’d been born 30 years later, I too might have tried to transition,” Rowling writes. “The allure of escaping womanhood would have been huge. I struggled with severe OCD as a teenager. If I’d found community and sympathy online that I couldn’t find in my immediate environment, I believe I could have been persuaded to turn myself into the son my father had openly said he’d have preferred.”

Any position that questions the validity of a trans person’s existence will be condemned by many in that community, regardless of the reasons or concerns of those stating that opinion. It is, for many, a cardinal, unforgivable sin.

For her views, Rowling has been labelled by some a TERF’ – an acronym coined by trans activists, which stands for Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist, implying hostility towards transgender people, a label she vehemently rejects.

“I want to be very clear here: I know transition will be a solution for some gender dysphoric people, although I’m also aware through extensive research that studies have consistently shown that between 60-90% of gender dysphoric teens will grow out of their dysphoria.” she writes.

What triggered her speaking out she says, was the Scottish government proceeding with its “controversial gender recognition plans, which removed the medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria as a requirement to change gender legally and fast tracked the process for changing gender. For Rowling, this bill – which was passed by the Scottish Parliament in December 2022, but vetoed by the British government in January 2023 – put woman’s lives at risk (allowing in her view a man to call himself a woman and walk into a female-assigned toilet) and was a “destroyer of women’s rights”.

“I spoke up about the importance of sex and have been paying the price ever since. I was transphobic, I was a cunt, a bitch, a TERF, I deserved cancelling, punching and death. You are Voldemort said one person, clearly feeling this was the only language I’d understand,” Rowling says.

Despite, these attacks, she has refused to back down, donating money to campaigns opposed to the stalled Scottish gender recognition Bill. She’s also dared authorities in Scotland to arrest her after calling a number of transgender women “men” – in apparent defiance of a new Scottish Hate Crime law which came into effect in April this year and which creates a “new crime of stirring up hatred against someone based on their disability, race, religion, sexual orientation transgender identity. (No action was taken against Rowling).

Has Rowling been treated harshly? Or has she deserved the condemnation she has endured by many?

Weighing things up in my mind, I would argue that she is not transphobic (as she has publicly stated) but certainly opposed to some forms of trans-activism where, in Rowling’s view it erases the idea of womanhood.

I feel she is entitled to this view and don’t feel there is as any legitimate reason to cancel Rowling or to stop encouraging young and old people to read her books.

You may feel the need to analyse the characters in her novels and their motives in light of her views on gender, and come to all sorts of conclusions about the author’s motivations or alleged prejudices, but let’s be honest, Harry Potter is not high-brow fiction. I don’t actually think its worthy of deep analysis. These are not books that need to be studying at University in the way that I studied the novels of Margaret Atwood or JM Coetzee or EM Forster.

JK Rowling’s Harry Potter books are simply brilliant adventure and fantasy stories and can be enjoyed as such without the need to read the subtext.

Reflecting on the all the controversy reminded me think of another famous children’s author, who has been vilified, partially re-written but thankfully never cancelled for their controversial views.

I’m referring Roald Dahl, who sold 300 million books and wrote some of the most beloved stories of all time: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, James and the Giant Peach, The Witches, Matilda and Fantastic Mr Fox to name just a few.

These books entertained and delighted me as a child and have been enjoyed with glee by my kids, both in the original written form and as movie and TV adaptations.

On the scale of unpalatable views, Dahl certainly trumps Rowling by some distance.

He was a well known and unapologetic anti-Semite who in an interview in 1983 said there is a “trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity, maybe it’s a kind of lack of generosity towards non-Jews”.

In 2020, Dahl’s own family apologised for his anti-semitism, but thankfully did not call for his books to be banned or burned.

That – in my opinion – is as it should be. And the same goes for the composer Richard Wagner (another anti-semite), or Pablo Picasso (a monstrous misogynist).

We do not have to love the artist to love and admire their art.

Rowling and Dahl inspire the imagination. They delight their readers. They celebrate bravery in the face of evil. They encourage adventure. And yes, you can take great offence in some of the characters in their books, or the motivations for creating them, but that should always be a personal choice, not a movement.

After all, you can always stop reading.