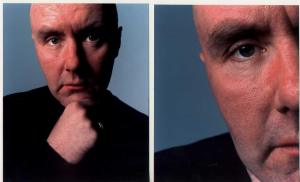

By strange coincidence, the day I picked up a copy of Billy Connolly’s autobiography “Windswept & Interesting” I saw on social media that the “Big Yin” had just turned 80.

It was quite a milestone for one of Britain’s most famous comics, actors and travel show hosts, and it seemed even more fitting that I should now be reading about his life.

I’ve long been a fan of his, enjoying his his hilarious storytelling stand-up comedy, entertaining travel documentaries as well as his more serious acting in movies like ‘What we did on our Holiday’.

He’s certainly a very talented individual, and from reading his book, comes across as warm-hearted and lovable person in his private life. This is in spite of many difficulties experienced in childhood including physical and sexual abuse and a later problem with drinking (no doubt caused by this trauma).

The title of his autobiography, which he wrote during lockdown, refers to the way his flamboyant appearance was described to him by a friend early on in his entertainment career.

It’s a moniker Connolly revels in and believes is an accurate description of a type of person he identifies with: someone with their own individual style and who doesn’t give a fuck (excuse my language, but I am paraphrasing Billy) what anyone else thinks.

“Being windswept and interesting is not just about what your wear,” writes Billy.

“It’s about your behaviour, speech, your environment and an attitude of mind. It’s perpetually classy – but it’s not of a particular class. It transcends class.”

Later, he says: “Once I’d realised that I was windswept and interesting, it became my new religion. It was such a delightful contrast to the dour and disapproving attitudes I’d grown up with. Instead of cowering under the yoke of ‘Thou shalt NOT!’ , I found a new mantra: ‘Fuck the begrudgers!'”

It’s an attitude of mind that runs throughout the book, fueling his success first as a musician (a career I knew nothing about) and then as often outrageous and daring stand-up comic. Without this psychic armour, Billy might never have made it out of the gloomy Glasgow tenement flat he’d grown up in and which he describes so well in the early chapters of the book.

As with many people of a certain age, the pandemic provided the opportunity for reflection and the time to sit down and think about their lives. He does so in a self-deprecating, warm way, that only sometimes veers off course into somewhat uninteresting (for me anyway) banalities and trivia, such as his favourite TV programs.

To this I am sure Connolly would say: I don’t give a fuck, it’s my story and I’ll choose what I write about. Fair enough, I would not want to be the “fucker that begrudges him”.

Billy Connolly’s story begins in a tenement flat in Anderston on the unloved south western outskirts of Glasgow, where he is raised by his aunts, one of whom is the sadistic Mona, a nasty woman who takes particular delight in physically and verbally assaulting her wee nephew.

Connolly finds himself in this unhealthy domestic situation after his mother runs off with another man, and his father is posted overseas during the war. Later, when his father returns, Connolly is forced to share a bed with him, and his horrifically and inexplicably abused.

It’s a shocking thing to be abused by our own father, but Connolly devotes only a few paragraphs to this incident (one of the surprising aspects of the book), leaving this dark chapter to be dissected by his second wife, the actress turned psychologist Pamela Stephenson, who wrote in more detail about it in her biography, Billy.

Connolly only mentions it again fleetingly, though other memories of his father surface such as family holidays. He only return to the very painful and confusing topic when his father dies.

It is of course a sign of Connolly’s strength of character, his tenacity and warm-heartedness that he does not allow such awful events to dominate his life, though those dark memories do fuel his excessive drinking.

In many respects the book is a chronicle of the people he met along his journey to self-acceptance, those individuals that impacted his life and his career in a positive and creative sense.

Among them were the welders he met while working as an apprentice on the Glasgow shipbuilding docks,

“The shipyards were full of patter merchants. That’s where I first really understood you could be incredibly funny without telling jokes,” recalls Billy.

He discovers he has a gift for making people laugh through his storytelling, a skill he gets to practice on stage before and in between gigs as a banjo and guitar player.

Of this musical career, I was blissfully unaware and so had no idea that Connolly teemed up with famed pop star Gerry Rafferty of “Baker Street” song fame to write music and tour as the folk band the Humblebums, to a fair degree of success.

While Connolly is keen to point out Gerry Rafferty’s far superior musical talents, there is certainly no doubt that Billy became by far the more famous and successful of the duo.

I also learnt to my surprise and astonishment that Billy does not prepare material for his stand-up shows, but pretty much just gets up on stage and starts talking.

It’s quite a gift, but no doubt gave his stand-up shows a daring, unexpected quality, as well as their freshness and spontaneity.

He writes of his first time of being onstage without Gerry as giving him a “lovely sense of freedom, just talking, singing and being myself”.

It’s the pleasure and enjoyment of storytelling, of being himself, which makes his autobiography so enjoyable for the reader, and especially the fan. There are also plenty of laugh-out-loud moments such as the hilarious “murdered my wife” joke he told on an appearance on the Michael Parkinson show in the 1970s (You can find it on YouTube).

Now an octogenarian living with Parkinson’s Disease and half his hearing gone, it’s good to know that Billy Connolly has turned into less of a grumpy old bastard and more of a opinionated cuddly bear, fond of swearing at the TV, but always eager to learn and discover new things, even in his sunset years.

Throughout it all, he’s remained true to his calling: windswept and interesting.