On April 10, 2021, my parents Ian and Cecile boarded a special repatriation flight from Johannesburg non-stop to Darwin to join two of their children and five grandchildren in the modern diaspora for South African Jews – Australia.

When they stepped on that plane at O.R. Tambo International Airport in preparation for a 17-hour flight to the top of Australia it was a quietly momentous moment in the history of my family, ending 155 years and five generations of physical connection with the beautiful, but troubled country at the bottom of Africa.

My parents’ departure from the Johannesburg Highveld, the place of spectacular summer thunderstorms and crisp, smoky winter days, of giant shopping malls and high-fenced suburbia – that great African metropolis and melting pot – was the final chapter in the Schlesinger’s South African adventure which started all the way back in 1866.

Isidor and Emma Schlesinger

In that year, adventurous 24-year-old Isidor Schlesinger journeyed from Silesia, a region in Central Europe that no longer exists (It’s now mostly part of Poland with bits in German and Czech Republic.) to seek and make his fortune on the goldfields of the Witwatersrand.

Silesia or Schlesien as it appears in German is the origin of our family name (and a fairly common Jewish surname). It’s the one affixed at the end of the names of my children – first generation Australians living in the tranquil Macedon Ranges north of Melbourne.

According to a book about my great grandfather Bruno Schlesinger written by his daughter Helga and grandson Keith, Isidor was born on the 10th March, 1842 either in Kempeny, a tiny hamlet 86.3 miles west of Vilnius, the present day capital of Lithuania, or somewhere in the province of Posen, in western Poland.

Travelling by ox-wagon, Isidor made his way across the “veld” to Pilgrim’s Rest in the Eastern Transvaal (now called Mpumalanga) to join a rush of prospectors at what was the region’s second major gold exploration site.

Whether it was in Pilgrim’s Rest (now a preserved museum town I visited as a child) or later at the Kimberley Diamond Mines in the Northern Cape (home to the famous Kimberley mine “Big Hole”) where Isidor made his fortune, it appears undisputed that he returned to Europe seven or eight years later, a rich man. He then married “tall, elegant” Emma Fasal in Bielsko (now called Bielsko-Biala) about 90 kilometres west of Krakow, Poland in 1874. Bielsko at the time had a thriving Jewish community that traced its roots back to the Middle Ages.

Isidor and Emma stayed in Eastern Europe, first in Katowice, Poland and later Troppau – now called Opava – in what is now the Czech Republic, where they set up a saw mill.

They also had three children: my great aunt and uncles Valeria and Feodor and my great grandfather Bruno Schlesinger, who born on the 22nd of March in 1879.

Later in 1889, in Budapest or Vienna, they had a fourth child, a daughter they named Leontine who became quite famous (she has a Wikipedia page) as the actress, writer and filmmaker Leontine Sagan.

Leontine is most famous for directing the ground-breaking 1931 movie Madchen in Uniform (Girls in Uniform) about a girl at an all-girls boarding school who falls in love with her female teacher. It doesn’t sound that risqué now, but imagine making such a film 90 years ago!

Returning to the adventures of Isidore, my great-great grandfather’s Czech sawmill venture was not successful and after moving to Budapest following the birth of Leontine, he dreamed again of the “wide open spaces” of South Africa.

My great grandfather Bruno Schlesinger remained in Europe, at the School of Mines in Leoben, Austria to complete his studies.

“Father never liked Europe, and the wish to get back to his beloved South Africa grew so strong that he decided to return alone,” wrote Leontine in her autobiography, Lights and Shadows

“When he had retrieved his financial losses, he would come back to us, or we could follow him.

Isidor returned to the South African goldfields in 1891 to reclaim his fortune. His family joined him eight years later.

Leontine writes that the family travelled to a “little corrugated iron house in the veld” that was the Kroonstadt railway station (now a large town between Bloemfontein and Welkom in the Free State Province) where they met their father again. The family then travelled to Klerksdorp, a small Afrikaans town in what is now the North West Province where gold was discovered in 1885 (and with a surprisingly rich Jewish history). Here Isidor owned the bar at the Freemason Lodge.

It was at the time of the First Boer War between the British Empire and the Boer or Dutch colonies, but it spared the German and Austrian immigrants, who were considered neutral outsiders.

Writes Leontine of her father: “One could not have imagined a man less suited to his job. He was a dreamer by nature, cared little about wealth, and felt happiest when he could sit with his pipe by the open veld-fire or with a book on the stoep. His friends included Afrikaners, Englishmen, and a few Germans, who had lived in the country for many years and who shared both his love for South Africa and his indifference to Europe. Their conversations circled around their business, the share-market in Johannesburg, politics, and that soft, gentle gossip which is a feature of every small town.”

Bruno and Else Schlesinger

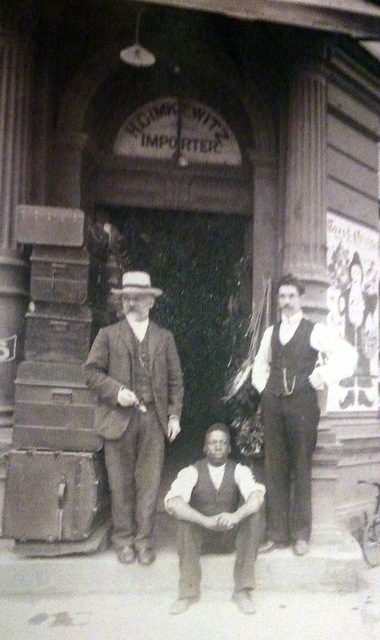

My great grandfather Bruno, who had by then joined his family in Klerksdorp, married Else Gimkewitz (born in Berlin in 1882) after a whirlwind courtship in November 1907. He’d also by then secured a position at one of the Witwatersrand gold mines.

Their daughter Helga, my great aunt, was born nine months later in 1908. I had the great pleasure of meeting Helga a few times in the 1980s and 1990s. I remember her as a charming and fiercely intelligent woman with a shock of white hair. (Helga died in 1998).

According to a story narrated by Helga in the book she co-authored about her father titled “Man of Tempered Steel”, Bruno, my great grandfather, stopped a Chinese mine labourer from stabbing him with a knife. “Bruno knocked it out his hand. None of the underground workers ever rebelled again.”

What provoked this attack is unclear, but this vignette of a swashbuckling, fearless figure is matched by photos of my great grandfather, who looks handsome and tough.

A few years later, the Schlesinger clan moved to the wilds of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) to prospect for gold. Here they lived in primitive thatched round huts or “rondavels” as they were called by the locals.

In another perhaps apocryphal tale told by Helga, Bruno lost his way in the bush on his way home one day and had to sleep tied to a branch in a tree after being stalked by a lion. He awoke in the morning to find the lion resting at the base of the tree. He managed to scare the lion off (or it got bored) and he made it home alive.

In a primary school project I created about my family called “My family roots” I wrote that Bruno “loved the natural life and was not very fond of towns and cities. He used to go for long walks through the countryside and often took his family for picnics in forests and woodlands”.

In September 1909, my grandfather Rolf was born at the Queen Victoria Nursing Home in Johannesburg. Less than a year later, in August 1910, Isidor died of an unknown cause and was buried in the old Braamfontein Jewish Cemetery, not far from where I and my sister Deena attended university at the mighty Wits (University of the Witwatersrand). Had I known my great grandfather was buried nearby, I would have sought his gravestone out.

My great, great grandmother Emma died thirty years after Isidor in August 1940 at the Florence Nightingale Nursing Home in inner city Hillbrow. This is very near to the Florence Nightingale maternity hospital where I was born on the December 6, 1973, my sister Deena on March 19, 1976 and my brother Dan on September 3, 1978.

When World War 1 broke out, my great grandfather Bruno, being Austrian, was sent to an internment camp at Fort Napier in Pietermaritzburg in the Natal province (now KwaZulu-Natal). He was later released on parole after a bout of serious illness.

He then fled to Lourenço Marques (now Maputo, Mozambique) while Helga and my grandfather Rolf, who were still small children, moved in with their grandparents, the Gimkewitzes, who lived in a small house in Hillbrow. A once thriving cosmopolitan suburb on the fringe of the Johannesburg city centre – a kind of Greenwich Village in the 1960s and 1970s I am told – Hillbrow had sadly, by the time I was 12 or 13, deteriorated into melting pot of drugs, violent crime and immigrants living in slum-like conditions after decades of neglect.

There are more Indiana Jones-like tales about my great grandfather Bruno, who during the First World War made his way on foot from Mozambique back to Hillbrow to his family, crossing rivers and swamps, and hiding in bushes to make the scarcely believable journey of 550 kilometres.

Despite his skills as a geologist and his toughness and resilience, Bruno was also prone to bouts of depression. While playful with his children, he was also a strict, authoritarian father, easily angered when they did not sit up straight at the dinner table, or did not use their knife and fork correctly.

In contrast, his wife, Else was more gentle with her children, according to Helga and Keith’s memoir.

In that same primary school project I wrote that Else studied literature and various languages at the University of Prague, and that later, when the family were struggling, she gave private French lessons at Kingsmead School, a girls-only school in Melrose in Johannesburg’s affluent inner northern suburbs.

“My great aunt [Helga] said that Elsa was resourceful, courageous and a dynamic lady who stood by her husband during times of need and was a very strong spirited lady.” I wrote.

My uncle Colin (Rolf’s oldest song) remembers that Else spoke with a thick German accent and loved singing German songs to him as a small boy.

“But I would always say: Granny, granny, you must speak English,” recalls Colin.

Despite his intelligence, academic qualifications and strong physique, Bruno was a poor businessman, naively lending money to the likes of Hans Merensky, a famed geologist and prospector who never repaid my great grandfather’s generosity. Bruno also invested in business ventures that failed.

“He was one of the guys with Hans Merensky who discovered platinum,” says Colin.

After lending money to Merensky, he received nothing in return when Merensky eventually made his fortune after discovering diamond deposits in Namaqualand, and vast platinum and chrome reefs at Lydenburg, Rustenburg and Potgietersrus,

Bruno also became heavily involved in the late 1920s diamond rush centred around Lichtenburg north west of Johannesburg and Grasfontein (near Pretoria) which became one of the biggest in the world. It drew in people like Sir Ernest Oppenheimer who founded mining giant Anglo American and whose family later took control of the world’s biggest diamond company De Beers.

“He made and lost money several times, that was a big part of [Bruno’s] life,” says Colin.

Despite his personal struggles, Bruno was highly respected and rose to the top of his profession. He headed up mining projects, and travelling to Portugal in 1927 to advise its president on silver mine projects in Lisbon. In that same year he appeared in the eminent, annual business publication of the day “Who’s Who South Africa”.

(Of course all this success should be set within the context of white privilege, where poorly paid black labourers dug out the gold and diamonds from the mines to make fortunes for the likes of the Oppenheimers and many others.)

Instead of investing sensibly in blue-chip stocks, Bruno played the Johannesburg Stock Exchange and duly lost all his money in the 1930 crash. He was forced to sell his grand home in at 49 St Patrick’s Road in Houghton Estate (now one of the city’s most exclusive addresses, where Nelson Mandela had a home) and rented for the rest of his life, a curse he seems to have passed down to me.

After experiencing heart problems in 1943, my great grandfather died in Muizenberg, Cape Town in January 1945, aged just 65. His wife, my great grandmother Else died 17 years later in Johannesburg.

Rolf and Nella Schlesinger

I have written a lengthy story (which you can read here) about my softly spoken grandfather Rolf and my glamourous grandmother Nella, detailing the breakdown of their marriage, after Rolf had an affair so I won’t repeat it here.

Nella and Rolf got married in Johannesburg in 1938. Nella was 30 at the time, and a year older than my grandfather.

She was one of five children born to Lithuanian’s Joseph and Chana Grevler (originally the family name was Grevleris). The Grevlers like other Eastern European Jewish families came to Johannesburg in search of wealth and prosperity on the mines.

Rolf and Nella had two children, my Uncle Colin who was born on the 18th December in 1939 and my father Ian, who was born on the 4th June in 1943 – both in Johannesburg.

Colin recalls that the family first lived in a house in Sandown, now an affluent northern suburb (home to Johannesburg’s shopping extravaganza, Sandton City) but that back in the 1940s was “out in the sticks, way beyond the northern suburbs”.

“Then we moved to a house at 18 Winslow Road, Parkwood. We lived in that house for a while, including when Ian was born.” Colin tells me.

After that, the Schlesingers moved just a few streets down to a house at 14 Rutland Road, just a street away from the sporting fields above Johannesburg’s Zoo Lake (an iconic outdoor leisure spot for most Joburgers).

“It was an old house, with a corrugated iron roof that made tremendous noise when it hailed. I loved lying in bed listening to hail banging on the roof,” says Colin.

Out front was a garden and a tall oak tree, the kind that line many streets of “leafy” Parkwood and neighbouring Saxonwold, two of Johannesburg’s oldest and most desirable suburbs.

When their parents split up in about 1950, my dad and my uncle remained at the Rutland Road house with my grandmother for many years. My grandfather moved into a flat where he had something akin to a nervous breakdown, and later rebirth as kinder, more loving version of himself (again you can read more about this in my earlier blog post).

My dad, who excelled at sports, especially swimming, cricket, soccer and rugby left the Rutland Road house when he went to study veterinary science at the University of Pretoria’s Onderstepoort campus, an hour’s drive to the north. Being an Afrikaans speaking university, my dad became fluent in the language.

After he graduated in 1969, he spent two years in England completing his apprenticeship. My uncle stayed at home with my grandmother while he completed his undergraduate in chemical engineering at Wits University.

Colin left home after completing his masters and marrying Sheila Cobrin in 1962. The young couple lived in a flat in Joubert Park, in the middle of the Johannesburg CBD. After that they headed overseas first to London, where Colin spent two years at Imperial College and then a year at Rice University in Houston obtaining his doctorate in chemical engineering. They then returned to Johannesburg, where Colin worked for African Explosives (AECI).

Having originally intended to stay in South Africa for just three years, Colin and Sheila ended up staying for 17 years in Johannesburg, during which time my cousins Ruth and David were born in 1968 and 1970.

They lived in a house in Parkmore, in the northern suburbs, across from a big, sloping field with enormous grey electricity poles. I remember many family gatherings, including Shabbat dinners at their home and playing in the backyard and swimming in the pool, where a little black poodle named Jet, would bark at us playfully. They are very happy memories.

The first Schlesingers to leave

Eventually, after rising up the ranks at both AECI and in the chemical engineering sector (my uncle was President of the Institute of Chemical Engineers) Colin decided in the early 1980s that it was time to leave South Africa. He was offered a job at petroleum giant Chevron and emigrated in 1983 (when he was 43) to Walnut Creek, a small city in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Nine years old at the time, I remember waving goodbye to my uncle, aunt and my dear cousins at what was then Jan Smuts Airport and saying “last touch” as our fingers touched through the glass partition in the departures corridor.

“It was really hard, we basically left our family behind,” says Colin.

“My mom came several times, but my dad never came to visit. I saw him in South Africa. That was the price you paid when you separate yourself from your family.

“Our families have been separated by time, by distance. It’s a big price to pay.”

In December 1987, when my parents were on the cusp of emigrating to Toronto, my mom and I visited Colin at his home in Walnut Creek as part of trip to Canada and London (my first ever overseas jaunt at the ripe old age of 14). There’s a great photo I have somewhere of my cousin David and I sitting opposite each other on the train with big grins on our faces after we’d had a meal in Chinatown in San Francisco. It was quite an adventure for a young lad like me.

Later, in 1994 when I travelled to the US as part of a 21st birthday present I hung out a lot with Ruth at her place in Downtown San Francisco, where she was worked part-time as a bike messenger.

Ruth now has two girls – Lily and Tula – and lives in Sebastopol, a semi-rural town about an hour north of San Francisco, with her husband Ross and a menagerie of farm animals. Ruth has built up a thriving Chinese medicine practice in Sebastopol, a profession well suited to her empathetic and warm nature. In November 2019, before the pandemic, Ruth and Tula came to Australia, and got to know my children, as we explored the local sites of the Macedon Ranges.

We have remained close despite the tyranny of distance and the long gaps between seeing each other.

My cousin David, who I have not seen since I stayed with him in Los Angeles in 1997 (among other things, he took me to Hawthorne Grill, which he featured in the opening and closing scenes of Pulp Fiction and we went to see the movie Con Air) lives in Corona, a suburb of LA near Ontario Airport.

Armed with a business degree from the University of Southern California and an auto-technician’s diploma from Wyoming Tech, David has risen up the ranks at engineering contractor and infrastructure giant Parson and is a project manager in its rail division.

He is married to Flor and has four children, a stepson James, David Jr (who I met as a small baby at my Uncle’s wedding to Cecile in 1997), Shaina and Ethan. His eldest son James, has two children of his own, making David a grandfather! While we have lost touch, I have very warm memories of David, especially his big smile and ability to make me laugh and I hope to re-establish our relationship.

Larry joins the emigration train

It would be another 17 years before the next Schlesinger left South Africa, that being me.

But before I get to that I should talk a little about my parents, my family and my childhood, which was a happy and secure one.

My dad, after completing two years in England working as a country vet (enjoying a life akin to the covers of those James Herriot books I like to imagine) returned to South Africa in the early 1970s and shortly thereafter met my beautiful mom in 1972.

Their meeting came about when my dad visited his friend David Berstein, a fellow vet.

Here he was asked if he’d like to meet a gorgeous, young pharmacist from Benoni by the name of Cecile Ann Hyton. My mom was the daughter of Harry (my Zaida) a devoutly religious, and somewhat reserved man who instilled in me (alongside his son, my Uncle Yoel who taught me my Bar Mitzah torah reading), a deep appreciation of my Jewish heritage and its customs. My Zaida was one of 10 children, born in 1903 in Lithuania to cheesemakers, Zuzza and Zippa.

I sadly never got to meet his wife, my Bobba Lily who passed away suddenly in 1971, two years before I was born. Lily (her maiden name was Brown) was born in Willowmore in the Eastern Cape, but moved to Benoni when she was young.

Returning to my parent’s matchmaking. Their happy fates were sealed by my mom’s Benoni High School chum Lena Berman and her husband Ron (who now live in Toronto with half the former Benoni Jewry of that era).

“After our first meeting, Ian came to our house to check on our dog, who was sick – I think the dog might have died. I’m not sure,” Cecile recalls.

Despite this early mishap, the dashing couple were soon engaged and married in a joyous celebration at the Benoni Town Hall, where my dad’s good friend and another fellow vet Brian Romberg was his best man.

I arrived on the scene soon on the 6 December 1973. My birth card says it was 7.40am in the morning when I made my first appearance in the nursing ward of the Florence Nightingale Maternity Hospital in Hillbrow.

My favourite story of my birth is the one my mom tells about her cousin Temmy Lipschitz.

“Temmy couldn’t remember if I was now Cecile Schlesinger, Cecile Rothschild or Cecile Oppenheimer, so she guessed and sent a congratulation card to ‘Cecile Oppenheimer”. If only!

My parents who had been living in a flat across from Germiston Lake, in the small mining metropolis of Germiston, bought a small brick house on Doak Street in the suburb of Hazel Park, where I spent my first few years.

The strongest memory I have of those early years, apart from lots of cuddles and kisses, was getting my head stuck in the bars of the small gate put in front of the steps leading up to the living room. Oh, and there was also the minor incident of a fire in my bedroom – caused by the heater setting the curtains alight – that almost brought about my premature demise.

With my cute-as-a-button freckly sister Deena coming on the scene a few years later (March 19, 1976) and my equally adorable baby brother Dan arriving on September 4, 1979, the Schlesingers need a larger pad and so we moved into a much bigger house with a large backyard and swimming pool at 25 Grace Avenue in Parkhill Gardens.

The street was lined with Jewish families. My best friend Jonathan Bennett andhis family lived just a few doors down (my first sleep over at their house was notable for me forgetting, one important item…my pajamas) while at one end of the street were close family friends the Stupels and the Freinkels. In between there were the Friedmans and at the other of the street were the Saffers.

Germiston at the time had a thriving Jewish community and grand old Moorish-style synagogue on the edge of the city centre. I was a regular Saturday morning Shabbat attendee for much of my childhood, where the brunch spread after the prayer service of kichel (a sugar-encrusted large yellow cracker) topped with even sweeter chopped herring was worth the effort of sitting through the synagogue service.

Often Jonathan and I would walk into town after brunch, where we stop to visit his father Dicky who worked on Saturdays in the local hardware store. The store had for some reason an enormous bag of monkey nuts (peanuts in shells) that we would plunder. On a number of occasions we went to see a movie at the 21st Century cinema, a classic old place in town. The first movie we saw on our own was Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Last Ark.

Back at home on Grace Avenue, we were a close knit family, celebrating our birthdays together (all three of us got presents no matter whose actual birthday it was). My mom would also bake a cake creatively decorated in the theme of our choosing.

All three of us attended Colin Mann primary, a whites-only government school where the Jewish kids were exempt from the Christian Morning Prayer service and instead hung out in the library. All of us were prefects.

I ended my primary school years doing a comedy skit in the school hall with Jonathan Bennett about journalists who were struggling to get a scoop for the local paper (who would have guessed, I’d end up with a newspaper career!).

In the skit, one of the journalists jumped off the building to his death and either I or Jonathan remarked: “Great, now I finally have a story for paper!” What were we thinking?

Our childhood was full of family holidays, mostly to Umhlanga Beach near Durban on the Natal north coast, where most of the Germiston Jews went for their seaside holidays. The Umhlanga Sand hotel was the place to be in the 1980s, whether it was ordering Cola Tonics and Lemonade at the pool, playing ten pin bowling or piling our plates at night at the legendary hotel buffet. I remember that hotel so well as I do the beach, where I would swim for hours in the rough surf, and head to the rock pools to search for fish and crabs. In the afternoon, we’d return to our holiday apartment, me with a bright red sunburnt face. I remember the African ladies selling their traditional beaded jewelry on blankets spread out along the walkway above the beach (black people were of course banned from actually sitting on the beach back then) and the ice cream vendors that walked up and down selling frozen granadilla ice lollies and other delights.

All of us attended King David Linksfield, the main Jewish day school in Johannesburg, where I studied Hebrew and Afrikaans.

In 1991, after I’d finished High School and started out at Wits University, we moved from Germiston to a five-bedroom house on Club Street, below Linksfield Ridge, where we were again surrounded by Jewish families and friends.

I started off studying architecture, but, after a number of false starts, ended up with a Bachelor of Arts degree majoring in English and Psychology and completed in 1996.

In 1997, the year both my grandmother Nella and my close friend Darren Serebro passed away, I abandoned plans to work part time (I lasted a day at CD Warehouse, a legendary music shop opposite the Rosebank Mall), and romantically write a novel, and instead scampered off to the US to work as a camp counsellor. I was employed for two months at Bnai Brith Beber Camp in Mukwonago, Wisconsin as an assistant art teacher, and was frequently hungover from visits to the local tavern. After completing my one and only dalliance with the world of teaching, I bought an Amtrak pass and railed it around the US visiting places like New Orleans and Boca Raton, where I stayed with friends I had made at summer camp.

I returned to Johannesburg in 1998 to study a one-year diploma in business management at Wits Business School, worked for a year for an online media company called I-Net Bridge and then became the second of the Schlesingers to leave the leafy Joburg suburbs for London on a two year UK working holiday visa, that turned into an unexpected permanent migration overseas.

It started with four years in London where I scribbled away for a weekly Accountancy industry magazine on Broadwick Street, Soho in the heart of the West End, drank lots of lager in smoky pubs and made frequent excursions to Europe with my best mate Jason Lurie. I lived for most of that time in Hendon, near the end of the Northern Line, in a flat above a kebab shop.

How I ended up in Australia is a story full of details I won’t bore you with. It suffices to say it was in pursuit of a disastrous relationship forged at an evening creative writing class in Holborn.

That had a fairytale ending though when one evening I met my beautiful and talented wife Larna, in Sydney at the Lord Nelson Hotel at The Rocks, a historic maritime quarter next to the CBD one evening in 2006. We moved in together soon after and were married in 2010 in Clyde, a small town on the South Island of New Zealand about an hour or so from Queenstown. Our red-headed sweetheart Edith (Edie) was born at the Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne on April 19, 2012. Our darling son Rafferty was still born at full-term on February 1 2014 (the saddest moment in our lives). Aubin, our handsome little tyke was born in Melbourne on the 19th June 2015 and gorgeous little Gwen made her appearance on July 30, 2018 – at the Sunshine Hospital in suburban Melbourne.

My sister Deena, having obtained her Law degree at Wits University married Larren in Johannesburg in a lavish wedding in 2001 and became a “Sher”. The newlyweds moved to London that same year – a year after me – but stayed in the British capital for decade forging successful careers and had two children there, a cherubic daughter Keira (born on November 29, 2008) and a very sweet son Jamie (March 28, 2011).

The Shers moved to Sydney, Australia in 2011, soon after Larna and I had returned from a round-the-world backpacking trip in 2010 (read all about it here if you’re keen) to settle in Melbourne, and later the “village in the valley” – Gisborne – about an hour to the north.

My brother Dan, who studied Business Science at the University of Cape Town and always beat me soundly at chess, won an unexpected US Green Card in the Green Card lottery. He moved to New York City in October 2006, where he lived on the Upper East Side with his girlfriend Courtney, a Floridian from Boca Raton. They married at a fancy five-star resort in Miami in December 2010 and then two children – a daughter Lexi born in 2014 and a son Ari, born in 2016. They New York Schlesinger clan quit the Big Smoke a few years ago, and bought a house in Rye Brook, a village in Westchester County, about an hour north of Manhattan.

The departure of my brother left my parents Ian and Cecile as the last of the Schlesingers in South Africa. Now empty nesters, they happily carried on with their careers and busy social lives with their huge circle of friends, trading in their big home on Club Street for a compact townhouse with a small garden in nearby Senderwood.

Over the next two decades, my parents were frequent overseas travellers, making annual pilgrimages to London, New York, Sydney and Melbourne to see their children and grandchildren. When not physically there, they kept in regular contact via phone calls, Skype video chats and text messages. Never has a birthday, anniversary or important event in our lives been missed. None of us could have asked for more devoted or unconditionally loving parents, a commitment demonstrated when they temporarily moved to New York for about six months in 2011 when my brother was battling Leukemia, a disease he overcame with great courage and bravery.

As they grew older, and our families larger, Ian and Cecile made the decision about five years ago to apply to become permanent residents of Australia, a costly, exhausting and lengthy process involving lawyers and migration agents, and mountains of paperwork.

When they did eventually become permanent residents, and were beginning the process of selling their home, and making the move to Sydney, the pandemic struck, confining them to their townhouse. To our great relief and theirs, they avoided getting COVID and passed the time happily, it seems, in each other’s exclusive company.

Amid the stress of worrying about their safety, and knowing we would not able to go to them if they fell ill, it was my sister who managed to get them on that special flight from Johannesburg to Darwin. In what seemed like a snap decision, they were on the plane, and heading for a new life in their early and mid-70s, the last of the Schlesingers to leave South Africa.

They touched down in Darwin on the morning of April 11 and after a two week compulsory stay at the Howard Springs quarantine facility, flew down to Sydney to be with my sister and her family.

Never ones to look back, though they miss South Africa and their life-long friends dearly, my parents have made new lives in the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney.

“We moved here to be with our family,” is my mom’s simple, but poignant view on things.

That they have adapted so well to a new country is still remarkable to me. Though they have been here just over a year, it feels in a way as if they have always been here. They have a huge circle of friends and lead busy social lives (a contributing factor no doubt to them both getting COVID a few months ago)

About a month ago, they got in their white Kia hatchback and headed south over two days through the NSW hinterland, passing scenery not entirely dissimilar to the rugged South African countryside, to visit us in Gisborne. My sister and her family also made the journey by car a week a bit later, and all of us – my parents, two of their children and five grandchildren – spent five wonderful days together.

My mom will say that was the whole point of them saying goodbye to South Africa, the country we all still love deep in our hearts, where Isidore Schlesinger sought his fortune all those years ago.