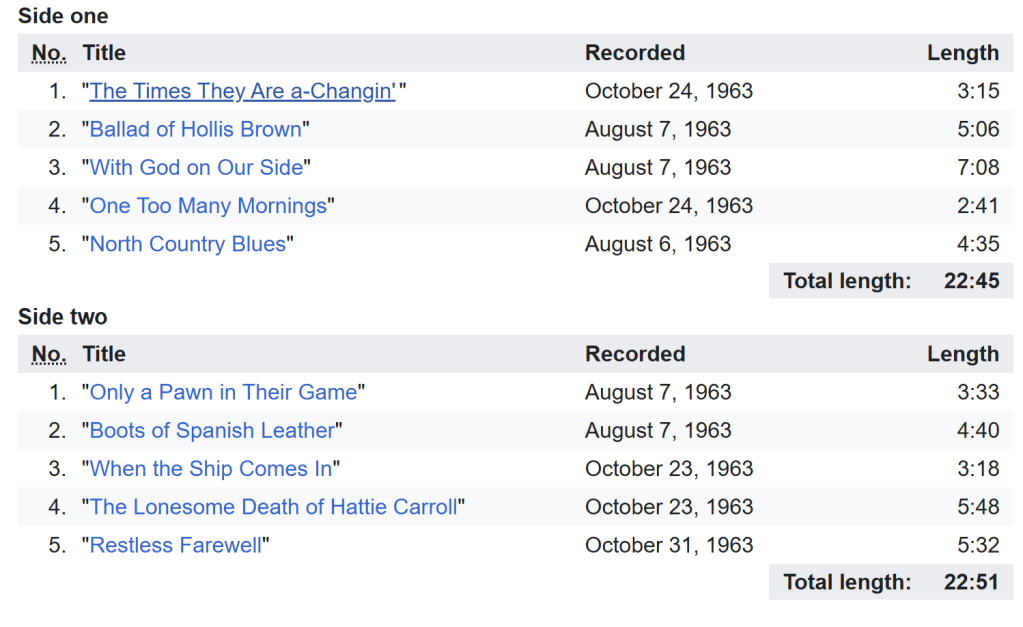

Title: The Times They are a-Changin’

Length: 45min, 36s

Number of songs: 10

Best tracks: The Times They are a-Changin’, Ballad of Hollis Brown, With God on our Side, North Country Blues, Boots of Spanish Leather, When the Ship Comes in, The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll

If I had to choose just one track: The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll

Freshlyworded rating: 9/10

Thoughts:

While the title track from this album is rightfully one of Bob Dylan’s most famous and revered songs, for me the hero track and an absolute masterpiece on this album (and surely among his best songs ever) is “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”.

Running just under six minutes, Dylan tells the story of the murder of Hattie Carroll, an African American barmaid, killed in a drunken rage in a Baltimore Hotel in February 1963 by 24-year-old Wiliam Zatzinger, a wealthy, white tobacco grower – and the injustice fuelled by racism that followed.

The song is a perfect combination of vivid poetry, acoustic guitar and Dylan’s plaintive, soulful voice.

Dylan wrote the song just six months after Carroll was murdered and it no doubt struck a chord among the civil rights movement at the time. Every sentence of the song is wonderful.

Zantzinger killed Hattie Carroll, Dylan sings: “With a cane that he twirled around his diamond ring finger” and after his arrest “Reacted to his deed with a shrug of his shoulders”.

He contrasts the Zantzinger’s wealth and high society connections with Carroll’s role as a servant “Who carried the dishes and took out the garbage”.

A few months later, “in the courtroom of honor” Dylans sings of the judge who “Stared at the person who killed for no reason” and then in a devastating line “handed out strongly for penalty and repentance William Zantzinger with a six-month sentence”.

As he tells the story of Hattie Carroll’s murder Dylan sings the repeated refrain: “But you who philosophize, disgrace and criticize all fears Take the rag away from your face, now ain’t the time for your tears.”

After singing how Zantzinger literally got away with murder, Dylan ends the song with: Oh, but you who philosophize, disgrace and criticize all fears. Bury the rag deep in your face for now’s the time for your tears“.

Just brilliant!

I listened to this song and all the other nine tracks of this album whilst walking my dog along quiet country roads and sleepy suburban streets in Lancefield north of Melbourne (where I live) and on holiday in Birregurra, a small town in the Otways region of Victoria. Both were the perfect backdrop for letting the wonderful storytelling songs of this album seep deep into my bones.

Alongside the Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, I of course loved The Times They Are-a-Changing, a universal anthem about profound change that’s coming to society. At the time it was recorded, this change was the civil rights and anti-war movement but it’s wonderful lyrics still inspire people today who are pushing for change amid the punishing regimes governing the world:

Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is rapidly agin’

Please get out of the new one

If you can’t lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin’

I also loved another haunting, narrative song, “Ballad of Hollis Brown” which tells the story of a poverty-stricken South Dakota farmer and the events leading up to a desperate act.

“With God on Our Side’ is a song that like “The Times They are a-Changing” reverberates loudly today, with its mockery of how believing in God justifies acts of war and America’s superior moral position.

“North Country Blues” is a wonderfully melodic, yet dark song sung in the first person about growing up in an iron ore mining town, where the work eventually dries up and the mine is closed

“Only a Pawn in their Game” is another powerful political song about the murder of a civil rights activist Medgar Evars, while another favourite track of mine on the album is the very catchy “When the Ship Comes in” which has a happy and triumphant feel to it.

The slow and contemplative “Restless Farewell” is a fitting end to a brilliant album, and also a great way to end an evening country stroll.

For me, this is Dylan’s best album of the three I have listened to and reviewed so far. Incredible that he was only 22 and 23 when he wrote and recorded all these amazing tracks.