It was both refreshing and a relief to read that even a great writer like Kazuo Ishiguro, winner of both the Booker Prize and the Nobel Prize, did not think that highly of his strange detective novel “When We Were Orphans”.

“It’s not my best book,” Ishiguro said after it was shortlisted for the 2000 Booker Prize.

Having demolished Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day in a single reading many years ago (as near perfect a novel as you will ever come to read, accompanied by a fine motion picture adaptation) it is not hard to see why he made this observation.

It’s a very odd, disjointed and at times completely baffling book, with periods of rather logical storytelling following by very strange Kafkaesque episodes where things seemingly simple and straightforward – like travelling a short distance from one place to another – take on these long, slow, nightmarish journeys that never seem to end.

Not that there are not a lot of very interesting and enjoyable aspects to When We Were Orphans, plus there is that wonderfully precise and elegant prose of Ishiguro to keep you reading during the bemusing bits.

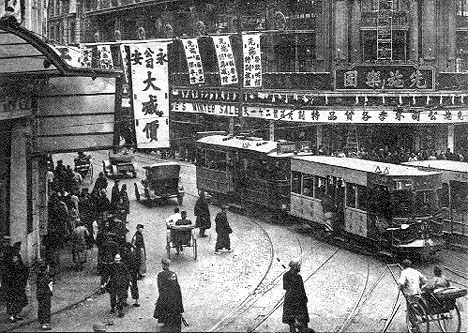

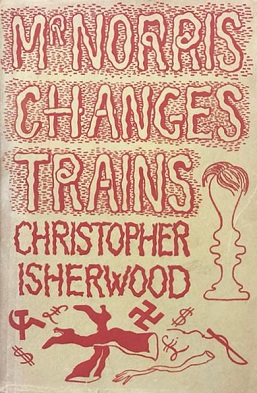

To summarise the plot, the book tells the story of Christopher Banks, who after being orphaned in Shanghai as a young boy in the early 1930s (when both his mother and father disappear from the city’s International Settlement in sinister circumstances), returns to England where he is educated and becomes a famous crime-solving detective.

Determined not be to be “diverted by the more superficial priorities of London life” Banks nonetheless falls for the charms of enigmatic socialite Sarah Hemmings – an orphan like himself – whilst becoming something of a minor celebrity for his ability to unravel cases.

The book weaves between Banks’ case solving pursuits in the English countryside, his intermingling in the upper echelons of London society, and with memories and flashbacks of his adventurous Shanghai childhood in the sheltered International Settlement. Here he remembers the times spent playing with his Japanese friend and neighbour Akira, with whom he forms a deep almost brotherly bond.

Banks also returns to recollections of the grand colonial mansion he lived in as a young boy and the events that led to first his father’s sudden disappearance and then soon after that of his feisty mother – a beauty in an “older, Victorian tradition, “handsome” rather than pretty.

Christopher’s father worked for a European shipping company called Butterfield and Swire, which was (according to the author) secretly involved in the flourishing Opium trade. Butterfield and Swire was a real company that transformed into a global multinational. Swire unsuccessfully sued Ishiguro in an attempt to get him to change the book, which implied the company turned millions into addicts and made vast profits in the process.

Before Banks’s father disappeared on his way to work, his mother had become vocal and outspoken about the activities of the company he worked for.

“Are you not ashamed to be in service of such a company?” he remember hearing his mother yell at his father. “How can your conscience rest while you owe your existence to such ungodly wealth?”

Twenty years later, and after having adopted an orphaned child Jennifer as his own daughter, Banks decides to return to Shanghai in 1937 at the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War (and as a great war looms across Europe) to solve the most important mystery of his life: his parents disappearance. He believes grandiosely that solving this crime will have far-reaching repercussions including averting the coming world war catastrophe.

In Shanghai, mingling among the snobbish expat community, at dinner parties, the war appears to be just over the horizon and drawing nearer. Ishiguro builds up an oppressive atmosphere as machine gun fire and explosions are heard not far away.

“Another thunderous explosion had rocked the room, provoking a few ironic cheers. I then noticed a little way in front of me, some French windows had opened and people had pushed out to the balcony.

“Don’t worry Mr Banks,” a young man said, grasping my elbow. “There’s no chance of any of that coming over here.”

Against the backdrop of the looming onset of war, Banks somehow believes that his parents are still locked up in a house in Shanghai by an opium warlord, despite 20 years having passed since their disappearance. He eventually locates the house he believes they are being held captive in and then the book descends into this Kafka-esque nightmare, where the house Banks believes his parents are in can be sighted through the bombed out ruins, but reaching it appears a never-ending hellish journey.

“Then I came upon a hole in a wall through which I could see only pitch blackness, but from which came the most overwhelming stink of excrement. I knew that to keep on course I should climb through into that room, but I could not bear the idea and kept walking. This fastidiousness cost me dear, for I did not another opening for some time, and thereafter, I had the impression of drifting further and further off my route.”

In his review of the novel, the Pulitizer Prize winning literary critic Michiko Kakutani wrote that ‘When We Were Orphans “has moments of enormous power, [but] it lacks the virtuosic control of language and tone that made ”Remains of the Day” such a tour de force.

“Indeed the reader is left with the impression that instead of envisioning – and rendering – a coherent new novel, Mr. Ishiguro simply ran the notion of a detective story through the word processing program of his earlier novels, then patched together the output into the ragged, if occasionally brilliant, story we hold in our hands.”

Certainly, I learnt a bit about life in Shanghai before the war, and the strange existence of the “International Settlement”. Also, I knew little about the Sino-Japanese War, which ran for eight years between 1937 and 1945 and was one of the most bloodiest in history.

But the novel itself, was a strange mishmash of a personal story set within historical events given an almost surrealist makeover that never really jelled for me (unlike the Remains of the Day, which so elegantly meshes the blind devotion of a loyal butler to an aristocratic employer wishing to promote Nazi appeasement.).

“When Banks goes back to Shanghai, we’re really not quite sure if it’s the real Shanghai or some mixture of memory and speculation,” said Ishiguro in an interview about the book.

It certainly baffled me.

Disappearing into Julian Barnes’s 2011 Booker prize-winning novel,

Disappearing into Julian Barnes’s 2011 Booker prize-winning novel,