When I was unexpectedly offered a job at The Australian Financial Review in July 2013 I jumped at the opportunity to write for the country’s top business newspaper.

Alongside this excitement, I also remember having this unsettling feeling that perhaps I was joining a national publication near the very end of the newspaper industry, certainly the print one.

Might I be one of the last print journalists hired by the AFR before everything went digital?

Nonetheless, I was thrilled to have an opportunity to join the workforce at Fairfax Media, one of Australia’s great publishing dynasties and to forge out a career in print media for as long as I could.

At the time I was approached by the AFR, I was working for an online publication called Property Observer (now part of urban.com.au), which had been launched two years prior by the former long serving Sydney Morning Herald property editor Jonathan Chancellor. It was part of an umbrella of brands owned by Eric Beecher’s Private Media (Others in the PM stable include well known news and opinion website Crikey).

Somehow my name had made its way to the decision-makers at the AFR – I am grateful to whom ever suggested me as a replacement for departing property writer Ben Wilmot (now commercial property editor at The Australian and whom I had the pleasure to meet for the first time in September).

I had an informal interview with Matthew Dunckley (then the AFR’s Melbourne bureau chief, now deputy editor of The Age) at a café on Degraves Street, and after signing an employment contract a week or so later, and after seeing out my last few weeks at Property Observer, I flew up to Sydney for a week of training and induction, and to meet my new Sydney-based property colleagues on the newspaper.

I remember the chatter in the industry and in rival newspaper media columns at the time was all about when the Fairfax printing presses would stop rolling seven days a week while the company, helmed then by former AFR journalist and editor Greg Hywood, was in the throws of a massive and at times painful digital transformation that would result in a number of voluntary redundancy rounds in the immediate years after I joined.

(There was also talk at the time that mining billionaire Gina Rinehart – as she climbed up the share register – might buy Fairfax. But following a long battle with the Fairfax board and management, her interest in the company eventually petered out and she sold out of Fairfax in 2015).

Incredibly, on my very first day in the Sydney office (at the time Fairfax was based at Pyrmont) I sat next to veteran journalist and multi Walkley Award winner Pam Williams.

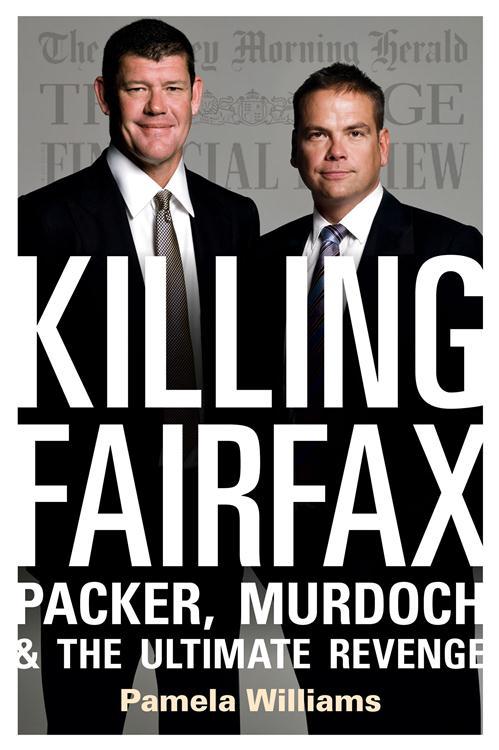

Pam’s blockbuster business book Killing Fairfax, which detailed how Fairfax Media had missed out on opportunities to invest in dotcom businesses like realestate.com.au and SEEK that would go on to be worth billions more than the 170-year-old media company had just been published complete with grinning photos of billionaires Lachlan Murdoch and James Packer on the cover.

I remember introducing myself to Pam and having a short conversation with her, whilst trying to get my head around the idea that she’d returned to the company she’d written so scathingly about in her book (which I read a few months later and reviewed on this blog). Later I would come to understand that this was part of what made Fairfax great; it’s unswerving belief in quality journalism, and Pam is certainly one of the best.

My first week in Sydney was spent learning how to use the antiquated publishing system known as Methode, meeting my boss Rob Harley, who was the paper’s long-serving and highly influential property editor, as well as many other journalists who would become friends and colleagues. I also wrote my very first article for the paper – a story about First Home Buyers – before flying back home to Victoria to join the paper’s Melbourne bureau and meet the journalists whom I would work alongside for many years.

The AFR occupied the Eastern corner of the third floor at 664 Collins Street opposite Southern Cross Station. On the other side of the floor was The Age, while upstairs were Fairfax’s radio stations including 3AW.

My first few weeks were spent meeting people in the property industry – agents, developers, investors – as I tried to build up a contact base and generate exclusive stories for the paper. There was back then and still is today a competitive, but highly collegiate mindset at the AFR, an attitude which helped me find my feet and carve out a niche of my own.

I’m somewhat embarrassed to say that for a little while after I joined the AFR I cut out and kept a folder of all my articles that appeared in the paper. It’s a practice I abandoned many years ago though I confess that I still get a kick out of seeing my name in print.

Initially it was quite hard getting scoops – we were a big property team in the early days – and being the newest member of a crew of crack reporters meant I had to find beats and niches that I could make my own.

At the same time as I was finding my feet and trying to show my value as part of the property team, Fairfax Media was trying to write the wrongs identified so glaringly in Pam Williams’ book and find new revenue opportunities in the digital world whilst print revenue continued to fall.

In 2014, Fairfax Media returned to profit and announced its move into video streaming on demand (to take on the likes of Netflix) via a joint venture with Nine Entertainment that would result in the launch of Stan.

That year was particularly tough one for me personally as we lost our second child Raffy to stillbirth in February, but I was heartened by the outpouring of support from my colleagues at the AFR when I returned to work after a few weeks of compassionate leave.

“Everyone from the top of the newspaper down is thinking of you,” I distinctly remember Rob Harley telling me.

Later that year I went on my first and to date only junket (or famil as they prefer to call it) to Bali, where I flew business class for the first time and sat next to The Australian‘s legendary restaurant critic John Lethlean. John was great company on the flight, but I recall was distinctly unimpressed with the food, while I thought everything was fantastic.

I spent two nights at the new Double Six Hotel (the reason for the trip) with a gang of Aussie journos, eating out at a plethora of fancy restaurants, trying out spa treatments and being chauffeured around amid the chaos and congestion that was Seminyak.

In 2015, I was lucky enough to be accepted into a mentoring program offered at Fairfax, and was given great guidance by senior Age journalist Michelle Griffin, (now Federal Bureau chief at the Sydney Morning Herald). We’d catch up for coffee in the café downstairs and focus on feature writing, which I always found challenging. Michelle was full of great tips and encouragement. These included suggesting I reading The Wall Street Journal’s The Art & Craft of Feature Writing by William Blundell.

Michelle is one of a number of highly experienced writers and editors who have provided advice, tips and encouragement over the years.

In August 2016 I interviewed the founder of British real estate disruptor Purplebricks, Michael Bruce when he came to Melbourne to launch the Australian business with a promise to revolutionise the way property is bought and sold through its fixed-fee model and online platform.

Over the next three years I reported in dozens of articles on the rise and fall of Purplebricks, which left Australian shores in 2019.

Covering the Purplebricks roller coaster journey Down Under was one of the highlights of my AFR journalism career (rumour has it my face was on a dart board at Purplebricks HQ in Sydney)

I should point out that soon after Purplebricks landed in Australia, our editor Rob Harley surprised everyone by announcing his decision to retire from the paper after an incredible 29 years. One of the most knowledgeable people in the industry and also one of its most influential and well-respected, Rob was a mentor to everyone on the team, and a generous sharer of his time and insights. (He continues to write for the Financial Review, penning a regular property column).

Upon Rob’s departure Matt Cranston took over as property editor for a couple of years before Nick Lenaghan took on the role when Matt took up a position as first economics editor in Canberra and then as the paper’s Washington correspondent. Both have been fine people to work alongside and like Rob, have been incredibly generous with sharing their knowledge and insight. (So too has been my property colleague Michael Bleby, whom I have worked alongside for most of the last 10 years. Michael lived for many years in South Africa, so we have that in common, plus a few words in Afrikaans.).

During those years of Purplebricks reporting, journalists at Fairfax and the AFR were undergoing their own rollercoaster ride as private equity firm TPG and a Canadian pension fund investor struck up talks to acquire the company.

Soon after, San Francisco-based private equity player Hellman & Friedman entered the takeover ring with a rival offer and it looked like we would all soon be working for new masters (noting with trepidation that private equity firms are notorious for cost cutting).

I remember also there was talk of the AFR being carved out of the company as a separate entity, perhaps through some sort of management buyout.

Thankfully (in my view), none of the takeover talks proceeded to binding offers and Fairfax moved on in July 2017 instead with plans to spin-off and float its online real estate listings business Domain.

Around this time I’d clocked up four years at the AFR, built up a solid contacts list and a half-decent reputation in the property sector for writing fair, balanced and interesting articles, occasionally with a bit of flair.

In June 2018, as traditional media companies fought back against the advertising power of Facebook and Google, Fairfax Media and Nine Entertainment revealed plans to merge their two businesses.

It turned out to be less of a merger and more of a takeover as the great Fairfax name was retired and we became, on December 7 of that year, Nine newspapers. On that same day Fairfax Media was delisted from the ASX, bringing about the end of one of the world’s great media dynasties stretching back 182 years to when John Fairfax purchased the Sydney Morning Herald in 1841.

While a lot of my colleagues were skeptical about the Nine merger/takeover and a potential loss of independence, I was excited about being part of a much larger media company that had not only newspapers, websites and radio stations, but also a clutch of commercial television channels.

In fact under the Nine banner very little has changed in how The Australian Financial Review has functioned. We remain fiercely independent, and most importantly the most-read business publication in the country. There is also (for me) a sense of security in being part of a true media giant. Indeed, those Fairfax redundancy rounds that were part of my first few years at the AFR have all disappeared replaced by expansion of our newsrooms.

In April 2019, we moved from the Collins Street end of Southern Cross Station to the Bourke Street end, occupying level 7 of the Nine building (a shiny glass-facaded Rubix cube-like structure) at 717 Bourke Street.

That I year I wrote my first “Lunch with the AFR” – a popular weekend paper feature where you sit down with an interesting subject and discuss their career. My subject was the property developer and adventurer Paul Hameister, conqueror of Everest, the Antarctic and the Amazon.

We had lunch at a trendy café in upmarket Brighton and Paul entertained me with his daring mountaineering feats, savvy business dealings and sage advice. Spending quality time with people as successful and interesting as Paul has been a part of the job I’ve enjoyed immensely.

(It would be another four years before I did another “Lunch with the AFR” when I sat down with another industry titan pub baron and reality TV star Stuart Laundy. We had lunch at his family’s Woolloomoo Bay Hotel at Wolloomooloo Wharf in August. It turned into a very entertaining chat with a dealmaker and storyteller extraordinaire).

Also in 2019, I penned a long feature article about myself that ran in the long weekend Australia Day edition. It was the entertaining story of how the least likely Aussie of all time became an Australian citizen. The article originally ran on this blog, and got a spit and polish (with a great photo below) for the version that ran in the paper.

The pandemic hit in March 2020 and as the national lockdown took hold we all vacated the office, laptops under our arms.

The great work-from-home era had begun.

It was chaotic working from home, whilst dealing with two children requiring home schooling – sometimes I wonder how I managed.

Without a closed off home office, I just had to work among the chaos. I remember on one occasion I was interviewing the CEO of a major listed company and right in the middle of the interview two of my kids started yelling and going mental. I tried to dash to a quieter spot but the noise just followed me.

“Larry, what the heck is going on at your house?” the CEO asked.

Embarrassed, I apologised profusely, hang up the phone and called him back later. As time went on though, people became more accepting of the challenges of working from home whilst also home schooling. I also just adapted, became used to the constant disruption and soon it became the norm.

When things began opening up again and we trickled back into the office, it was almost exciting heading onto to the train for the 1 hour commute from our home in Gisborne in the Macedon Ranges to Melbourne. Seeing people face to face was a thrill for a while, so was a visit to a café.

The pandemic and post pandemic years seemed to roll into each other – 2021, 2022 and finally 2023. It all seems a blur, probably because it was such a crazy, muddled time, when there seemed no clear division between work and home life.

Journalism is an industry well suited to remote working (I remember one colleague quietly relocated for a time to Noosa on the Sunshine Coast, but continued to write stories as though he were in Melbourne), and it can, in my opinion be an aid to productivity depending on the circumstances. Let’s not forget their are journalists who file in war zones and amid natural disasters.

The post pandemic years also brought a new skill to my repertoire – hosting interviews and discussions on stage at our annual property summit. This was at times nerve-wracking but also exhilarating speaking before an audience in the many hundreds, including many titans of the property industry.

Then in August this year, I suddenly found myself at the 10 year milestone. The years had flown by, and so much had happened both personally and professionally.

I’ve worked hard, but also been incredibly lucky to forge a career as a newspaper journalist amid all the seismic ructions that have reshaped how the industry functions.

Despite the minority who distrust the “mainstream media” and prefer their information from those shouting the loudest on social media, newspapers in Australia are still a very important part of the nation’s progressive democracy and a vital institution in holding those in power to account.

Long may the ride continue!

President Donald Trump, who has railed endlessly against the mainstream media’s criticisms of him through the popular mantra of FAKE NEWS recently turned to his attention to fellow Australian journalist Jonathan Swan, a former

President Donald Trump, who has railed endlessly against the mainstream media’s criticisms of him through the popular mantra of FAKE NEWS recently turned to his attention to fellow Australian journalist Jonathan Swan, a former