What an absolute joy and pleasure it is to read the Inspector Morse novels written by the late, great Colin Dexter.

I absolutely adored the television series and the wonderful portrayal of the curmudgeonly chief inspector by the imperial John Thaw, but the novels are marvelous in their own right.

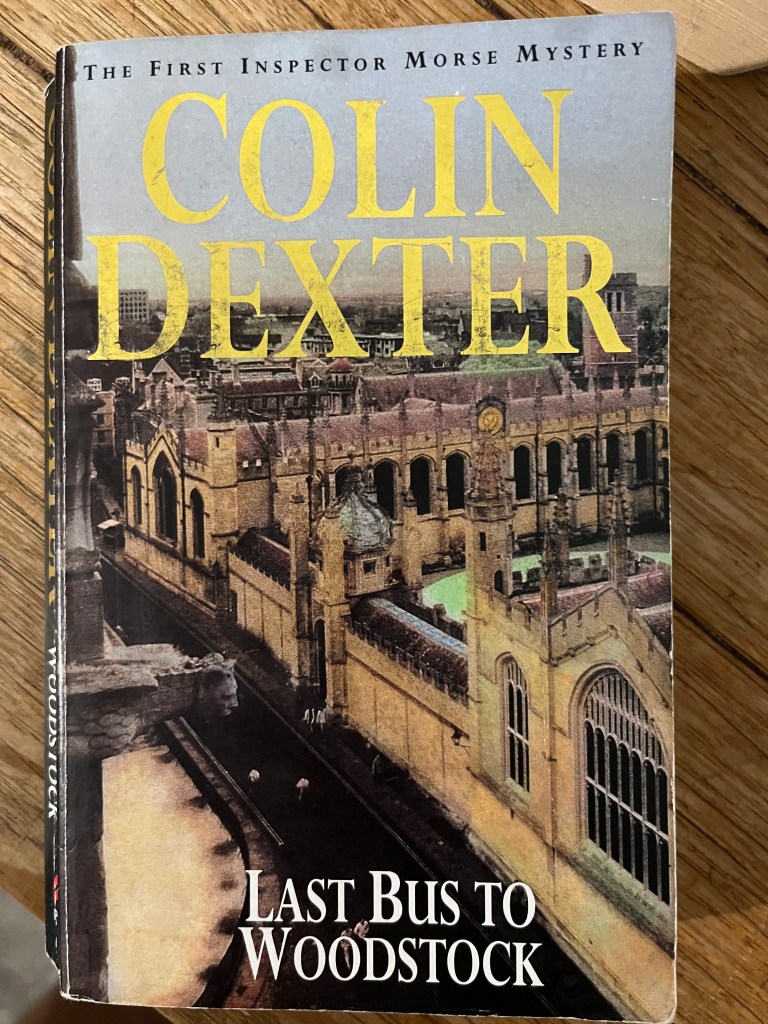

I read three in quick succession starting with The Daughters of Cain (1994) followed by The Jewel That Was Ours (first published in 1989) and Last Bus to Woodstock, the very first of the Inspector Morse novels, published in 1975.

(In 2016, I read my first Inspector Morse novel The Wench is Dead (the eighth book in the series), a rather unusual book as Morse is recovering in hospital and spends his time solving a Victorian murder mystery dating back to 1859. You can read my review here).

Having first watched the TV series and then delved into the books (it really should have been the other way round), it’s impossible not to imagine John Thaw as Morse and Kevin Whateley as his lanky, Geordie crime-solving sidekick Seargeant Robbie Lewis.

In the Daughters of Cain, Morse and Lewis investigate the murder of Oxford academic Dr Felix McClure, found stabbed to death in his North Oxford flat, the murder weapon nowhere to be found. Suspicion falls on three woman – his wife, his stepdaughter and his wife’s friend (all with motive) – and it’s up to Morse and Lewis to correctly identify the killer.

In the Jewel that Was Ours, American tourist Lauran Stratton is found dead of an apparent heart attack in her unlocked room at the Randolph Hotel. Later a precious jewel that she was to donate to an Oxford museum is found missing from her handbag. Stratton is part of a tour group of American retirees visiting historic cities of England. It falls to Morse and Lewis to unearth who among the group of unmerry travellers committed the robbery and why.

Interestingly, The Jewel that Was Ours is the only one of 13 Morse novels, which was first a Colin Dexter screenplay (filmed with the title The Wolvercote Tongue) and then later novelised.

In Last Bus to Woodstock a young woman is found murdered in the parking lot of the Black Prince, a pub on the outskirts of Oxford, after accepting a ride from a stranger. Suspicion falls on the young, devious man who discovered the body and a philandering Oxford don. Amid his investigations, Morse falls in love with a young nurse and gets to know, admire and berate Seargeant Lewis.

I loved the slowly unravelling pace of the feature length TV episodes – a much more realistic depiction of how crimes are solved in real life I suspect – and this kind of meticulous unravelling of characters and motives occurs in a similar fashion in the books.

Of course, Dexter throws in plenty of red herrings – and even the great Inspector Morse comes to the wrong conclusions from time to time. In The Jewel that was Ours, Morse is convinced he has identified the killer, who he arrests at a train station and drags into an interrogation room, only to realise that he has made a blunder.

I love the fact that he is both a brilliant man, but also far from perfect. He is easily seduced by a beautiful woman, frequently drinks too much, can fly into a rage with little provocation, but is also compassionate, kind and empathetic. He is also very funny, in a mostly cynical way:

In this comic scene from The Daughters of Cain, Morse is talking to Ellie, a young woman he has become infatuated with).

“Don’t you ever eat?” demanded Ellie, wiping her mouth on the sleeve of her blouse, and draining her third glass of red wine.

“Not very often, at meal-times no.”

“A fella needs his calories, though. Got to keep his strength up – if you know what I mean.”

“I usually take my calories in liquid form at lunchtime.”

“Funny, isn’t it? You bein’ a copper and all that – and then drinking all the beer you do.”

“Don’t worry I am the only person in Oxford who gets more sober the more he drinks.”

“How do you manage that?”

“Years of practice. I don’t recommend it though.”

All three novels were adapted into episodes for the television series, but I could only vaguely remember the plot twists, and so the identity murderer came as a complete surprise in each book.

But even if I had remembered the plots, the great thing about the Morse novels is the wonderful writing of Dexter. He really is a joy to read.

Dexter is master of delving into the personalities of his main suspects and of taking us into the mind of the brilliant Morse and the not-to-be-underestimated Lewis. He is also brilliant at his meticulous descriptions of crime scenes, painting vivid pictures in the mind of the reader.

“The body had been found in a hunched-up, foetal posture, with both hands clutching the lower abdomen and the eyes screwed tightly closed as if McClure had died in the throes of some excruciating pain,” is how Dexter describes the deceased murder victim in The Daughters of Cain.

Interestingly, there is very little physical description of Morse in the first novel. Instead, he comes to light through his personality and mannerisms.

Morse makes his first ever appearance on page 15 of Last Bus to Woodstock after he arrives at the crime scene in the courtyard of the pub.

“Five minutes later, a second police car arrived, and eyes turned to the lightly built, dark-haired man who alighted.”

The hard-working Lewis is already there, having arrived with “commendable promptitude”,

“[Morse] knew Sergeant Lewis only slightly but soon found himself pleasurably impressed by the man’s level-headed competence.”

“‘Lewis, I want you to work with me on this case,’ the Seargeant looked straight at Morse and into the hard, grey eyes. He heard himself say he would be delighted.”

And so, begins one of the great fictional crime-solving partnerships, one that would spawn another 12 novels (published from 1975 to 1999), a television series of 33 feature length episodes (from 1987 to 2000) and two TV spin-offs, Lewis (42 feature-length episodes from 2006 to 2015) and Endeavour, featuring the young Inspector Morse (36 feature-length episodes from 2012 to 2023).

(I have watched every episode of Lewis and thought it an excellent sequel to Inspector Morse, but I have not watched any Endeavour, though I hear it is possibly the best of the three.)

That’s an incredible amount of television viewing created out of a rather old-fashioned, curmudgeonly, middle-aged detective,

Colin Dexter, who makes a Hitchcockian cameo in almost every episode of Morse (he died in 2017) began writing mystery novels during a family holiday in 1972 after a career as a classics teacher was cut short by the onset of deafness

He claims that when he first started writing the crime novels, he had little idea of what Morse was actually like. “I’ve never had a very good visual imagination. I never had anyone in mind,” he said in an interview with The Strand Magazine in 2013.

“The only thing that was really important to me about Morse was that he was very sensitive and rather vulnerable,”

Dexter also revealed that much of the things that bring pleasure to his otherwise grumpy detective hero, are things that Dexter himself enjoyed: classic English literature, classical music, cryptic crossword puzzles and real ale.

“People don’t realise this. The greatest things in [Morse’s] life were [A.E] Houseman and Wagner. These were the things he would go home and listen to and talk about and that was me I suppose, but that’s about as far as it went. I never even wrote plots for my books. I always made sure that before I started writing a story I knew exactly how it was going to end. I never had any idea about what was going to happen in the middle but I knew where it was heading,” Dexter said.

While each of the four novels I have read so far are classics of British crime fiction, with meticulously clever plots and sub-plots and wonderfully engaging characters, it is Morse himself who is central to everything. Brilliant, sad, hilarious and tragic, he is a marvel.

Now to find and read the remaining Morse novels (they are devilishly hard to find!)

I recently read Presumed Innocent the New York Times best-selling legal thriller written by

I recently read Presumed Innocent the New York Times best-selling legal thriller written by

In 1990, when the movie of Presumed Innocent came out Time magazine featured Scott Turow on its June 11 cover calling him ‘the bard of the litigious age’. (It’s also become a popular crossword clue!)

In 1990, when the movie of Presumed Innocent came out Time magazine featured Scott Turow on its June 11 cover calling him ‘the bard of the litigious age’. (It’s also become a popular crossword clue!)