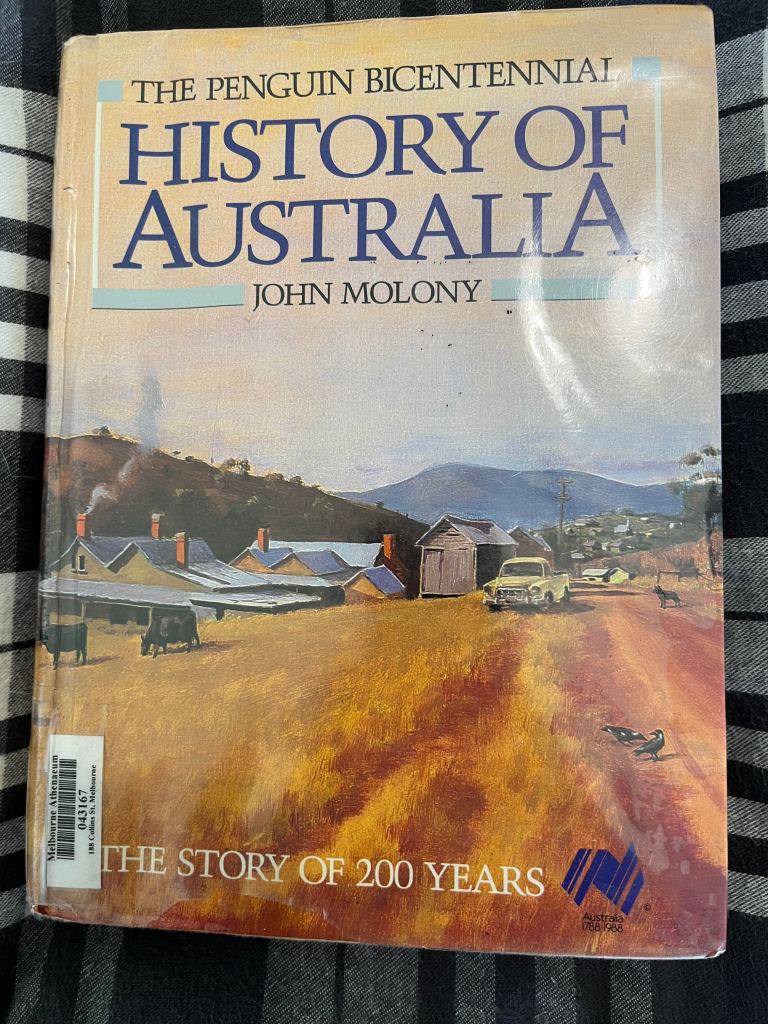

In one of the early chapters of respected historian John Molony‘s The Penguin Bicentennial History of Australia (which I reviewed here), a seemingly incredible story is reduced to just a few sentences.

It’s the early days of the colony, 1813 to be exact and Molony writes about the convicts being sent to Tasmania, or as it was then known, “Van Diemen’s Land”.

Molony writes: “The first direct consignment of 200 male convicts arrived in Hobart in 1812, but a vessel carrying female convicts was captured by an American privateer. The women were put down on an island in the Atlantic on 17 January 1813 and never heard of again.”

According to Molony, an entire ship full of female convicts had been taken prisoner and deposited on an unnamed island in the middle of the ocean, their fates an unsolved mystery.

I was utterly intrigued by this strange and disturbing story, and eager to know more.

While Molony did not have the luxury of Google when he wrote his book (published in 1987), he was a renowned historian and academic being the Emeritus Professor of History at the Australian National University. So my immediate instinct was to completely trust his version of events. But still the sentence nagged at me. How could a whole ship of female convicts completely vanish? Didn’t someone try to find out what happened to them?

While Molony may have dismissed it as just a footnote in the history of Australia, I was keen to find out as much as I could about the Emu, the convicts on board and the events that had sealed their mysterious fate.

Entirely untrue

Very quickly, I found a lot of information about what happened to the Emu, and I have to report that Molony’s simple verdict that the convicts onboard “were never heard of again” is entirely untrue.

In a fact, an entire book has been written about the ship and the convicts on board titled: “Journey to a New Life: The Story of the Ships Emu in 1812 and Broxbornebury in 1814, Including Crew, Female Convicts and Free Passengers on Board” by Elizabeth Hook.

Hook (now Beth Taylor } is a descendent of one of the convicts aboard the Emu, Jane Jones.

Jones, like so many of those sent to Australia, was convicted of a rather petty crime at a time when Britain was a highly unequal society, where the middle and upper classes lived well and the lower classes struggled to survive.

Aged just 17, she was convicted of theft in 1812 after she and a younger accomplice broke into a public house in London and were caught in the act of stealing a large quantity of food and money. Jones was sentenced to death, but because of her young age and being “of good character” (her father was a glassmaker) her sentence was commuted to transportation to the fledgling colony of NSW for life.

(You can read the entire Old Bailey trial transcript here).

She was put on the Emu, a merchant ship built in Liverpool which set sail in October 1812. Jones was one of 49 female convicts. Rather than never being heard of again – as Molony claimed – she did reach Sydney, but only in July 1814 and on a different ship, and after a hellish experience that lasted almost two years.

Molony was correct about the initial fate of the Emu. It was indeed captured by a privateer, the 18-gun Holkar, led Captain J. Rolland. A privateer was a US-government sanctioned ship whose task it was to steal British ships and their cargo.

The taking of the Emu occurred at particularly treacherous time to be sailing the seas as Britain was at war with the United States, a conflict sparked by maritime disputes and known as the War of 1812.

Journey to Cape Verde

As to that unnamed island in the Atlantic Ocean Molony says the crew and convicts aboard the Emu were dumped on, it was St Vincent (now Sao Vicente) in the Cape Verde islands, about 840 km west of Dhaka, Senegal. According to numerous trustworthy online accounts, the 22 crew of the Emu and the 49 female convicts were put ashore on January 17,1813 at Porte Grande.

Porte Grande is a bay on the North Coast of Sao Vicente, and is where the island’s main city of Mindelo is situated today. Discovered by the Portuguese in the 1460s, the Cape Verdes were populated by Portugese settlers who were allowed to keep slaves.

At the time the female convicts were put down at Porte Grande, the Portuguese-owned island was recovering as settlers returned following a devastating drought.

Final journey to Sydney

The female convicts and crew spent 12 months on St Vincent before being picked up by the Isabella and returned to Britain. Here they were put on a hulk (a floating prison) in Portsmouth Harbour for four months and then put on another ship, the Broxbornebury and transported to Port Jackson in the colony of NSW, departing in February 1814.

Beth Taylor, in her post on Convictrecords.com.au about her “3X great-grandmother” Jane Jones, notes that while there was no official record of what happened to the women convicts, their children and the crew during their stay on St Vincent, “an unverified report states that they were looked after by Catholic nuns. One of the women, Elizabeth King, died on the island on the 29th of January 1813”.

Taylor writes: “They arrived back at Portsmouth England (via a journey to Bear Haven, Ireland), about the 12th of October 1813, only for the authorities to be told the women were “….in a state of nakedness and inadvisable of their being landed…” They were kept on board in the harbour for a total of four months until another ship was made ready for a voyage to the Colony, which was the Broxbornebury in February 1814, along with an extra eighty-five female convicts.

Taylor continues: “Not all the thirty-nine remaining women from the Emu made the journey to New South Wales. Five convicts were transferred to the Captivity prison hulk ship in Portsmouth Harbour. Four of these women were granted Full Pardons and one died on the hulk ship. For the other thirty-four it had been a long voyage when they finally arrived in Sydney in July 1814, twenty months after first embarking on the Emu!”

After a long, exhausting and terrifying ordeal that lasted nearly two years. Jane Jones would have been just 19 when she arrived in the fledgling city of Sydney. She did, however, live long life in NSW, dying on the 24th of April 1868, aged 73. Her occupation is listed on convictrecords.com.au as “servant”.

The story of Jane Jones

I contacted Beth Taylor to ask if she knew of Molony’s book and his error about the Emu.

She replied a few days later that she had never heard of the book I’d read “so did not know about the mistake regarding the ship Emu“.

She went on to say: “I first heard about the Emu in the mid 1980s when I started researching my family tree & found my 3X great-grandmother Jane Jones was a convict onboard. The story had been passed down many generations & about how she had met her husband-to-be, a free passenger, John Stilwell, on the ship Broxbornebury.

“At that time, I did most of my researching at the Mitchell Library [part of the NSW State Library] in Sydney, but it wasn’t until years later when I found I had many other relatives, free & convict, on the Broxbornebury, that I looked into it further & attempted to confirm the story of the Emu.

“This was confirmed in The Convict Ships 1787-1868 by Charles Bateson, page 191. Quite a long story about what happened & it was first published in 1959.”

That’s almost 30 years before Molony researched and wrote his Australian history book.

Beth added that she undertook further research online in 2000, which she incorporated into the third edition of her book, published in 2014.

After corresponding with Beth, I came across another entry about Jane Jones on a website called immigrationplace.com.au, which fills in quite a few blanks about her rather extraordinary life as does a detailed entry on People Australia (a website of the Australian National University).

It seems that Jane’s luck changed when she met John Stilwell on board the Broxbornebury. Stilwell was a steward of the surgeon Sir John Jamison who was also travelling to Sydney aboard the same ship.

It appears Stilwell used his relationship with Sir John to secure her a job as a housekeeper at one of his properties, the Westmoreland Arms Hotel, where Stilwell was installed as publican and manager. The alternative, had she not met Stilwell, was to be sent to another hellish institution, the “Female Factory at Parramatta” where unmarried female convicts lived like slaves and in solitary confinement in an imposing sandstone building on the banks of the Parramatta River.

Jane Jones married Stilwell, had five children with him and received a full pardon from Governor Macquarie in 1820. Rather than leave the colony as she could have done, Jones stayed in NSW, had another six children with another ex-convict John Webster (Stilwell ran into financial problems, abandoned Jane and their children and returned to Britain in 1825) and later moved to Goulburn, where Webster became a butcher.

“John died on 28th February 1842 aged 44 years. Jane died of ‘old age’ in her house in Auburn Street, Goulburn on 24th April 1868 aged 74 years. It is believed they are both buried in the Presbyterian section of the original burial ground, Mortis Road Cemetery,” according to Immigrationplace.com.au.

Jones is just one of the 34 original Emu convicts who came to Sydney in 1814. There are fascinating stories of the other women who made it to Sydney aboard the Broxbournebury, some of which you can read here. Today hundreds if not thousands of the descendants of these brave women live in Australia.

Reconsidering Molony’s error

Returning to Molony’s error, I do wonder – given the fact there were texts available, and he was a very experienced historian – how he managed to get the story of the Emu so badly wrong. Charles Bateson’s book about convict ships, which Beth Taylor used as a reference for her own book, was published – as I mentioned earlier in 1959 – and would presumably been available to Molony.

It remains a mystery as to what source material he relied on to come to the conclusion that the Emu and its crew were put down on an island somewhere and never heard from again.

He might be a bit embarrassed about that error were he aware of it, but I am certain he would have been utterly intrigued, as I was, by the story of what actually happened.

I’m currently reading a second, more comprehensive Australian history book, titled Great Southern Land by Frank Welsh (published in 2004) and am intrigued to see if the story of the Emu is given more prominence, and whether Welsh got the facts correct! Stay tuned!