I loved reading David Lodge’s Nice Work, the third of his so-called “University Campus Trilogy” series of novels.

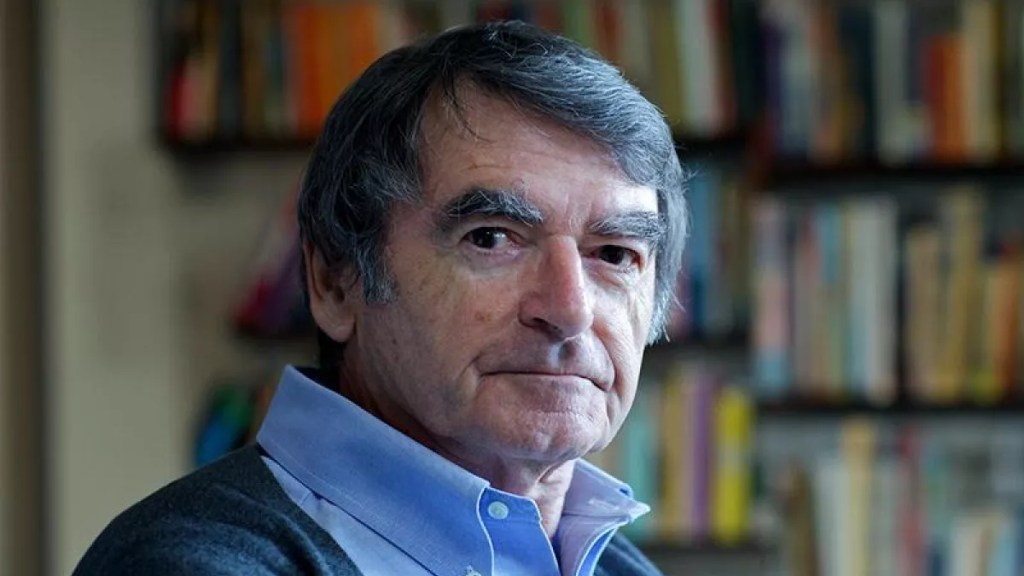

Published in 1988, it was shortlisted for the Booker Prize but lost out to Australian author Peter Carey’s Oscar and Lucinda. Lodge passed away in January this year, less than a month shy of his 90th birthday.

Nice Work is set in the fictional town of Rummidge, a large, industrial town in the north of England modelled somewhat on Birmingham.

The plot of the novel is centred around two characters, attractive and ambitious English lecturer and feminist Dr Robyn Penrose and Vic Wilcox, the grumpy, unhappily married managing director of a struggling steel parts manufacturing company.

The protagonists’ paths cross when Penrose, who is desperately trying to land a permanent job at the University of Rummidge agrees to take part in the “Shadow Scheme” a program devised to bridge the divide between elitisit world of academia and giant cogs of commerce and industry.

Every Wednesday, Penrose must drive to the offices of J.Pringle & Sons and shadow Wilcox as he goes about his day.

The novel is a modern and comic take on Elizabeth Gaskell’s 1854 novel North and South, about a woman who moves from the rural south of England to the industrialised north where she witnesses, in the fictional industrial town of Milton, the clashes between factory owners and workers amidst the industrial revolution.

In Lodge’s novel, Robyn Penrose – who ironically lectures on the industrial novel in English Literature but has never seen the inside of a factory – is appalled by the repetitive, menial work of men working in the cold and soulless J. Pringle & Sons factory she has been shown round.

Later, sitting in on a management meeting where she is only meant to be an observer, she starts arguing with Wilcox and his management team over plans to engineer the firing of a worker who is struggling to do his job.

“Excuse me,” said Robyn.

“Yes, what is it,” said Wilcox, looking up impatiently from his spreadsheet.“Do I understand correctly that you are proposing to pressure a man into making mistakes so that you can sack him?”

Wilcox stared at Robyn. There was a long silence, such as falls over a saloon bar in a Western at moments of confrontation. Not only did the other men not speak; they did not move. They did not appear to even breathe. Robyn herself was breathing rather fast, in short, shallow pants.

“I don’t think it’s any of your business, Dr Penrose,” said Wilcox at last.

“Oh, but it is,” said Robyn hotly. “It’s the business of anyone who cares about truth and justice.”

And so, Lodge, sets up the ideological battle between his two chief protagonists which plays out amidst the grim shadows of machinery, blue-collar men and cold and soulless sheds and the bustling corridors, hallowed lecture theatres and academic politics of Rummidge University.

It’s a delightfully funny battle full of exasperation and sexual tension as well as education as Wilcox teaches Penrose about the dirty world of industrial dealing and backstabbing, whilst Penrose expands his narrow view of the world and removes his stigma about the world of academia and learning.

And to spice things up, unhappily married Wilcox finds himself growing increasingly attracted to his younger shadow. (An early comic episode in the novel is Wilcox’s confusion when he finds his shadow is a woman and not a man, a fault partly due to the misspelling of Robyn’s name with the more masculine “Robin”).

One of the reasons the novel is so enjoyable is that both protagonists are likeable, basically decent and willing to shift their attitudes. Lodge also has plenty to say about the importance of education and commerce, theoretical points of view versus practical reality and the way one’s behaviours are shaped by the uncertainty of one’s lives: Wilcox’s job security is under threat from strikes, dwindling profit margins and cheaper competitor’s while likewise Penrose has only a temporary position at the university while older, less capable men have the power to deny her a permanent role.

Set against the backdrop of Thatcher’s education cuts and her battle to reduce the power of the trade unions, Nice Work is ultimately an uplifting novel about how people from vastly different backgrounds can come to understand a vastly different point of view – and end up not just friends, but perhaps, even for a time… a bit more than that.

And it’s a real pleasure to read. Lodge is a wonderful comic writer.

(Nice Work was made into a four-episode BBC min-series, which aired in 1989. I found all of the episodes on YouTube. I haven’t yet watched it myself).