The joke that sticks doggedly in my mind from stand-up comic Tom Ballard’s Saturday Night gig, ‘The World Keeps Happening’ is the one he made about 9/11.

The joke that sticks doggedly in my mind from stand-up comic Tom Ballard’s Saturday Night gig, ‘The World Keeps Happening’ is the one he made about 9/11.

Ballard, young, blonde, dressed in a t-shirt and black jeans asks: “Would 9/11 have been so bad… if they’d flown into the Trump Towers instead?”

(Queue: a low rumble of shock across the packed old theatre).

He qualifies this by saying the planes would be empty and so would be the Manhattan tower, except for Donald Trump, now president-elect Trump “alone, on the toilet, masturbating over a picture of his daughter.”

(Queue even more shock. But Ballard loves it). “Ooh a few Trump fans in tonight,” he muses.

Later, as his high-octane 90 minute set, which left no taboo unturned, drew to its close, he asked cheekily of his audience: ‘Have I managed to lose you all of you tonight?’

He hadn’t of course: almost everyone cheered loudly at the end including me. Perhaps they would have lynched him in Queensland or Ohio.

A night with Tom Ballard, as I found out, is not for the faint-hearted or easily offended. Certainly his stand-up material would set the right-wing old fogges in Western Sydney into a frenzy were he to perform it on the ABC, where he first cut his teeth as a Radio host on Triple J.

Ballard’s act swerves from embarrasing personal experiences mostly of a sexual nature (like the time an ex-lover texted him to say he had “gonorrhoea of the mouth and anus” and he replied to say he was all fine now after getting treatment, instead he replied to a youth worker with the same name, instead) to discussing how technology is ruining our lives (“I’m addicted to my iPhone, I even auto-correct myself when I speak”) to ticking off on racism, sexism and homophobia. (Ballard has hosted two episodes of popular ABC political talk show Q&A).

“No one assassinates politicians in Australia,” he says. “I’m not saying we should be doing that, but a bit of passion would be nice.”

He goes on to relate the disappearance of Harold Holt, the only Australian leader to die in office who disappeared while out for an ocean swim.

“We looked for him a bit and then said, uh, he’s gone. And that was that,” Ballard says with a playful shrug.

Back to the cringeworthy, Ballard related the story of a friend, who for some unknown, unfathomable reason thought it a good idea to eat two 24-slice packets of cheese in one sitting. The result: “He felt a bit unwell and had to go to the doctor”.

Here his friend was told that all the cheese had congealed into a solid mass – “He had a cheese baby” Ballard declares with unbridled joy at the audience’s revulsion, “and he would have it removed by caesarian.”

I confess I knew very little about Tom Ballard before the show though I recognised the face and name. (We – my wife and I – were lucky to pick up two complimentary tickets).

I quick read of his Wikipedia profile reveals that he grew up in Warnambool in country Victoria, is extremely smart (named Dux of the South West Region) and is passionate about a number of issues: vegetarianism, homophobia and cyber-bulling. He also once dated another of the country’s top comics, Josh Thomas the star of sitcom Please Like Me.

As with all really good stand-up comics he both mines his own personal experiences for comic material and uses comedy to make a point about the issues he cares about. (Not just that, he organised for volunteers from Refugee Legal to stand outside after the show with buckets to collect donations to support the work the centre does for refugees).

On inequality, he tells the story about a visit to Grill’d, the burger joint which allows customers to donate money to local charities through tokens they receive after ordering meals.

In this instance, he was in Warringah, on Sydney’s upper crust Northern Beaches where onion eating ex-PM Tony Abbott is the local federal member.

One of the ridiculous charity choices was to donate to the local school’s rowing club so that they could buy new kit.

“Sorry starving people of Africa…” Ballard bursts out with indignation, “the rowing club needs a hand” followed by an impersonation of spoilt, rich parents and their “desperate” kids.

“People rowing boats, these are the boats we should be turning back!” Ballard retorts with maniacal glee, delivering a scathing rebuke of the government’s tough approach to asylum seekers who come by boat.

His other suggestion, which I really liked was that we should ban all drugs, except for one day every four years – preferably on election day – when it should be a free-for-all.

“When I am on ecstacy, I just want to hug everyone,” he says.

His point being of course that we’re making some pretty bad choices sober, so why not try the other way.

Not a bad idea.

(A quick note: the show was recorded and will appear on streaming video service Stan at some point as part of its “One Stan Series”. So look out for it.)

When the

When the  It’s impossible for me to think of Inspector Morse,

It’s impossible for me to think of Inspector Morse,

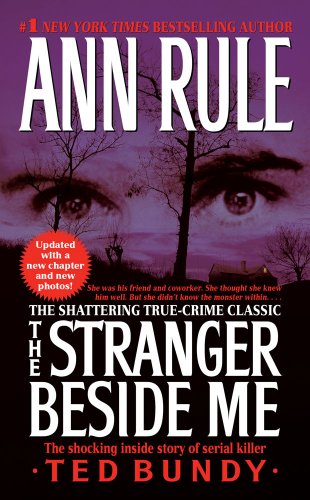

Among the best books ever written about true crime and serial murder must surely be Ann Rule’s The Stranger Beside Me, about the

Among the best books ever written about true crime and serial murder must surely be Ann Rule’s The Stranger Beside Me, about the

An unremarkable thing occurred on the train last week. A young Asian lady nearly fainted in the crowded, airless rush hour carriage.

An unremarkable thing occurred on the train last week. A young Asian lady nearly fainted in the crowded, airless rush hour carriage. The front cover of my edition of

The front cover of my edition of

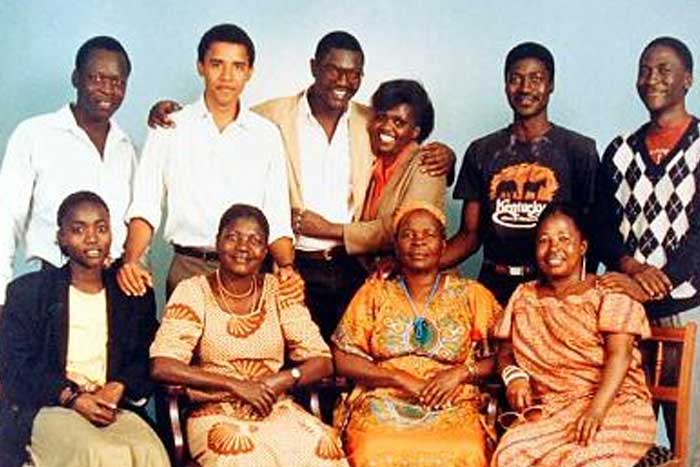

Even if Barack Obama had not gone on to become the first African-American president of the United States, he would have lived a remarkable life.

Even if Barack Obama had not gone on to become the first African-American president of the United States, he would have lived a remarkable life.

The abiding image, the one that sticks doggedly in my mind having read

The abiding image, the one that sticks doggedly in my mind having read

It always amazed me how cheap products are in the numerous ‘Bargain’ shops on our busy high street in the cosmopolitan Melbourne suburb I live in.

It always amazed me how cheap products are in the numerous ‘Bargain’ shops on our busy high street in the cosmopolitan Melbourne suburb I live in.