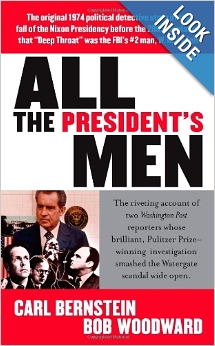

“All the President’s Men” – Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s account of how they uncovered and reported the Watergate Scandal in 1972 and 1973 in the Washington Post and brought down President Nixon and his goons – should be compulsory reading for any journalist wanting tips on how to break a big story. It’s practically a ‘how to’ manual on investigative journalism.

“All the President’s Men” – Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s account of how they uncovered and reported the Watergate Scandal in 1972 and 1973 in the Washington Post and brought down President Nixon and his goons – should be compulsory reading for any journalist wanting tips on how to break a big story. It’s practically a ‘how to’ manual on investigative journalism.

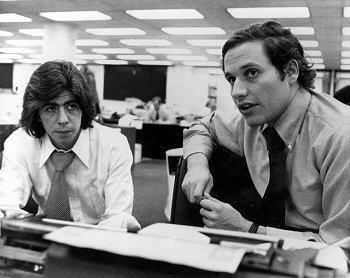

I don’t know if they still make journalists like Bernstein and Woodward, but even in the digital age, where research and information is just a search term away, the techniques, tricks and cunning they employed still apply. Truly great stories don’t come from Google.

I should be upfront and say, that I did not find ‘All the President’s Men’ an easy book to read.

Firstly there are the sheer number of characters and the very convoluted plot. In the inside introductory pages of my paperback edition there is a list of 51 people – presidential staff, advisers, aids, campaign directors, lawyers, editors and prosecutors – who were the main players in the scandal. I found I had to constantly turn back to the beginning of the book to remind myself of who each person was as the plot diverged into a myriad different strands.

This may sound harsh, given Bernstein and Woodward’s reporting (and others on the paper) helped the Washington Post win the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 1973, but it’s also not incredibly well written. Perhaps writing a 300 page book gave crack newspaper reporters – accustomed to writing 500 – 1000 word articles – too much leeway to tell their story. There’s too much information crammed into paragraphs and too many minor incidents that get in the way of the overall plot – a good, tight edit would have done marvels to the finished work.

That being said, it does provide some incredible insights into how these two brave, foolhardy, and belligerent reporters dug down the deepest of rabbit holes to uncover the truth.

Married journos need not apply

The first thing that’s apparent is the long and strange hours Bernstein and Woodward put in to crack the story. Neither of them were married at the time or in relationships, nor did they have children. This made it easier for them to work late into the night in the offices of the Washington Post, or drive out to the outlying suburbs of Washington or jet off to Miami or Los Angeles to track down and interview people and give up their weekends in pursuit of a story.

Anyone journalist today married or in a relationship would find it impossible to put in the hours they did – they would either end up divorced or entirely burnt out, or both.

Woodward famously would head out well after midnight to meet up with “Deep Throat” (later revealed to be the FBI’ no.2 man Mark Felt) in deserted car basements to verify information or seek help with stories.

Both journalists also had no qualms about ringing up legendary Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee at 2am and asking if they could come over to discuss an idea or situation.

Hit the phones relentlessly. Put in the hard yards.

In the book, Woodward and Bernstein recount countless hours spent calling people on long lists, hoping to come across someone in the White House, Justice Department or some friend of a friend willing to share confidential information with them.

By beginning at the top of a list and working their way through it, Woodward Bernstein would eventually find someone willing to speak to them. Sometimes they’d spend the whole day just telephoning people in the hope of finding a useful contact. In this way, they built up an incredible network of insiders. This is how they worked:

Each kept a separate master list of telephone numbers. The numbers were called at least twice a week. Eventually, the combined totals of names on their lists swelled to several hundred, yet fewer than 50 were duplicated.

Think laterally, be creative

Bernstein and Woodward were very savvy and had to be because the might of President Nixon, his ‘men’ and the CIA were out to prevent the ties between Watergate and the White House cover-up ever being revealed.

Sometimes they crossed the line and veered into the murky borders of the unethical or illegal – for instance, when they contacted members of the grand jury investigating Watergate who weren’t supposed to talk to the press or on one occasion, Bernstein not identifying himself as Washington Post reporter.

(Read the actual newspaper article here.)

On another occasion, they met with chief prosecutor Earl Silbert in his fastidiously tidy office. Bernstein noticed a piece of paper on his desk that had as its letterhead the name of the company where bugging equipment for Watergate had been purchased. He used this information to write a story and was severely admonished by Silbert who called his methods “sneaky, outrageous and dishonest”. Bernstein apologised, but saw it differently:

Bernstein had learnt years before that the ability to read upside down could be a useful reportorial skill…

The point is that no opportunity was passed up. Every lead, idea or suggestion was followed up.

Get people to talk

Bernstein were masters at getting people to talk. One way, was to get themselves inside the house of a person they knew had good information, but was reluctant or too scared to speak and then find ways of staying and chatting. In one rather comical episode, they kept on ordering cup after cup of coffee in an attempt to prolong a conversation with the wife of an important person caught up in the conspiracy.

They write:

The trick was getting inside somebody’s apartment or house. There, a conversation could be pursued, consciences could be appealed to, there the reporters could try to establish themselves as human beings

Be daring out and outrageous

Bernstein and Woodward pulled some outrageous stunts and came close to going to jail.

My favourite one is towards the end of the book.

Following a day in court where the Watergate defendants are being tried, Bernstein and Woodward along with a couple of other reporters notice three of the defendants and their lawyer trying to hail a cab. Bernstein races down as they file into the cab and

…uninvited got in anyway, piling in on top of them as the door slammed.

But it doesn’t end here:

Bernstein arrived back in the office late Saturday (he had gotten into the cab on a Friday afternoon). He had gone to the airport with Rothblatt and his clients, bought a ticket on a flight one of them was taking, edged his way in by offering to carry a suitcase and engaging in friendly banter, and slipped into the adjoining seat. Bernstein did not have to press the man too hard to turn the conversation to the trial. The story came out in a restful flow of conversation as the jet engines surged peacefully in the background.

Talk about outrageous, but this was the way Bernstein and Woodward operated.

Not all their ideas paid of – and a couple almost sunk them.

They misread what they thought were confirmations from sources on at least two occasions (one involved a source agreeing to hang up after 10 seconds if the story read out to them was entirely true. The source hung up but misunderstood the instructions) with spectacular results. But most of the time they got the story.

Every word matters

Every word mattered to Bernstein and Woodward and to their editors. The lead (opening paragraph) had to be perfect and they would fight over words and phrases and re-write and re-write as deadlines approached. This, of course, would be a problem in today’s 24 hour news cycle, where posting stories quickly as well as accurately is the challenge.

However, the digital age has not dampened the importance of writing well and being able to tell an engrossing story in a few hundred perfectly chosen words, as Bernstein and Woodward did back then. The importance of ‘words’ is revealed in this revelation:

The two fought openly. Sometimes they battled for fifteen minutes over a single word or sentence. Nuances were critically important, the emphasis had to be just right…sooner or later however, (usually later) the story was hammered out.

And let’s not forget the end result of their endeavours, the resignation of President Richard Nixon

Loved reading this – it makes you want to go back to a time before the phrase ’24 hour news cycle’ existed.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment Alex, you are so right! A lot of good journalists and journalism has been lost due to 24 hour news cycle

LikeLike